NFL Analysis

6/22/22

12 min read

The Secret to Finding a Franchise Quarterback Part 2: Developmental Environment Prevails

It was a valiant surge toward the goal line. Carson Wentz, then the quarterback of the 10-2 2017 Philadelphia Eagles, who were trading knockout blows in the throes of a war in the L.A. Coliseum, found a glimmer of daylight between two ill-intentioned defenders.

Without hesitation, and with certainty of impending pain, Wentz propelled himself through the pair of punishers toward paydirt. In a blink, both the team and its Meek Mill-loving fans feared their championship Dreams had unfold and Nightmares had come true. With a division title costing the team its starting quarterback for the season, the thrilling win over the Rams felt like a Pyrrhic victory.

Well, until ole’ St. Nick Foles stepped in, that is.

In the ultimate reinforcement of the importance of the backup quarterback, Foles picked up where Wentz left off and led the team on a magical run all the way through the playoffs and up to the top of the Art Museum steps for a Super celebratory ceremony. It was a run rivaled only by that of a 1990 Jeff Hostetler, who, like Foles, was a former third-round pick who won a Super Bowl in relief of an injured starter.

To get the highest quality of quarterbacking, on that stage, out of a mid-round draft pick is rare. Very rare. So very rare, in fact, that research into all of the quarterbacks drafted in the middle rounds of the last ten drafts would suggest that it is actually more of an anomaly than an attainable objective.

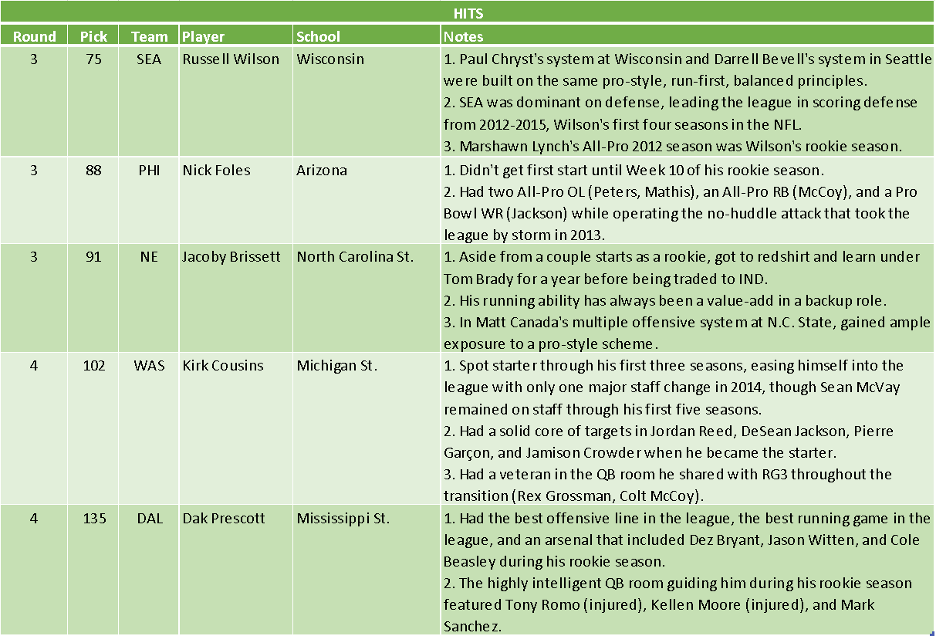

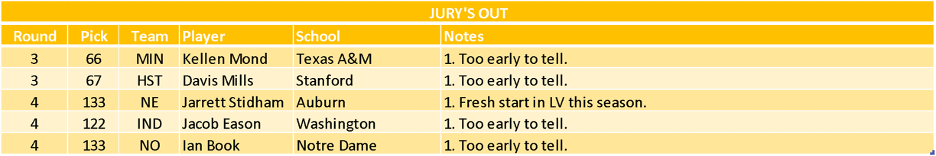

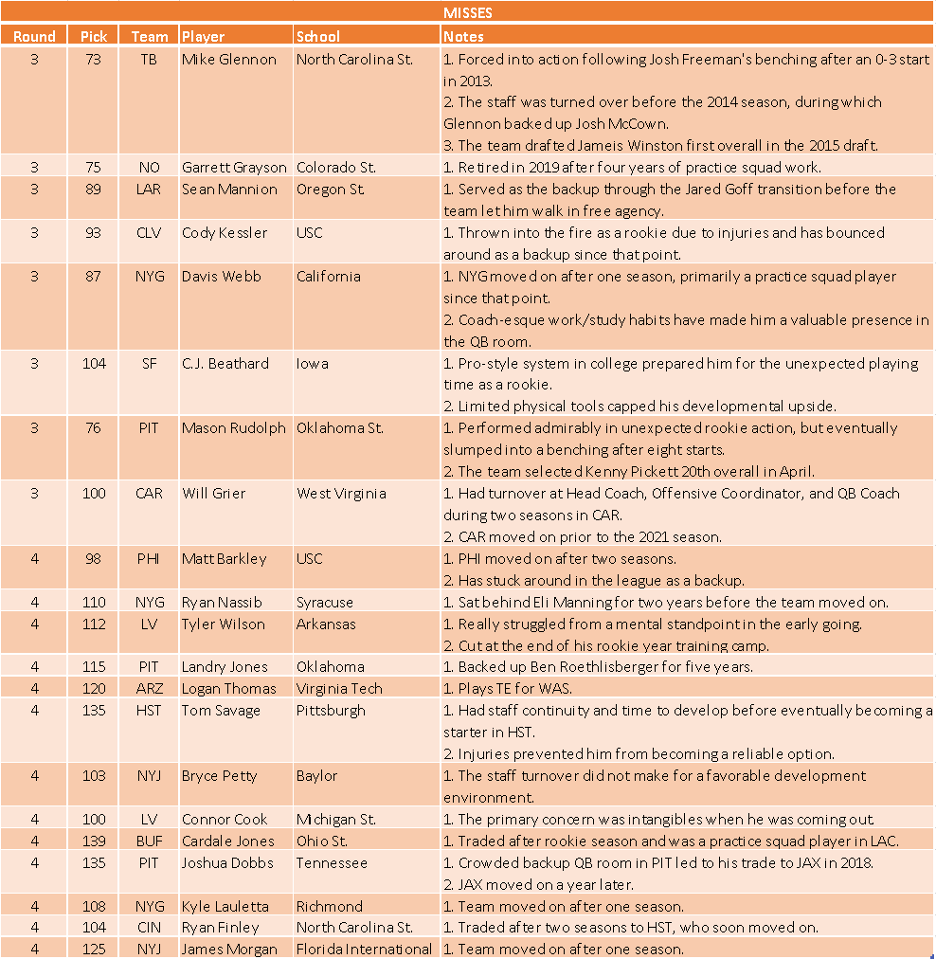

In a continuation of last week’s early-round QB Draft Research, a study was performed that looked into the last decade’s worth of signal-callers picked between the third and fourth rounds. The same process of discriminating the “hits” from the “misses” was followed; however, for that sector of the draft, hits were defined as those prospects who became functional players with whom a team can win provided there is ample talent around them. In other words, a hit in the middle rounds is a player a team would be thrilled with as a backup but would want to upgrade as a starter.

There was more subjectivity in this range as the inability to use second contracts as a proxy for success increased the ambiguity of performance evaluation. The goal, here, was to identify commonalities between the hits and the misses so that teams may make better-informed decisions on developmental starters or backups at quarterback in the middle of the draft.

Data

Hits

Jury’s Out

Misses

Discussion

Including the prized passers perched at the peak of the mid-round mountain, the usual suspects drafted in the third and fourth rounds at the quarterback position, by and large, tend to fit one of two profiles.

The first profile is that of the classic boom/bust prospect, the high-ceiling, low-floor collection of mesmerizing traits who needs an ideal development environment to put it all together. Think Mike Glennon, think Cardale Jones. The team who drafts him envisions a potential future starter who they were able to acquire at a cost well below the typical franchise quarterback asking price of a premium pick (or two, or three, or four).

The second profile is that of the polished student of the game whose current proximity to his ceiling is more attractive than the height of it. Think Kirk Cousins, think C.J. Beathard. The drafter hopes, at worst, the draftee is its steady backup of the future and, at best, is its “win with” starter who can build the bridge of time the team needs on its continued quest for a “win because of” starter.

Without any real indication of one profile finding more success than the other, the data, overall, shows a staggeringly disproportionate ratio of hits to misses. Drafting a quarterback in the middle rounds is a huge gamble, regardless of the profile. That said, some teams have won big on that bet, so the why behind this trend is as important than the what of it.

A few explanatory themes that leapt out from the analysis are highlighted below.

Themes

The Development Environment Prevails

A common practice among football media outlets is to produce “re-draft” pieces. These are articles that revisit a particular year’s draft and reconfigure how that draft “should have” played out, based on the performances of the players within that draft class. Late-round steals soar into the first round, and early round busts plummet far below where they were originally selected. It’s the perfect application of 20/20 hindsight, correcting the past with the very same wisdom it provided.

Interestingly, a dissection of the situations into which Russell Wilson, Kirk Cousins, and Dak Prescott, who were mid-round grand slams, stepped as rookies puts the legitimacy of all re-draft content in question. Not to take anything away from Wilson’s greatness, but consider the near-flawless development environment he found in Seattle in 2012:

- His rookie contract years coincided with one of the best four-year stretches of defensive football the league has ever seen.

- He was supported by a tremendous running game led by Marshawn Lynch, who was a Pro Bowl selection in each of Wilson’s first three seasons.

- He found a perfect system fit in Darrell Bevell’s offense that mirrored the Paul Chryst-led system he operated at Wisconsin.

- The Head Coach, Offensive Coordinator, and QB Coach remained on staff through his first four seasons.

- The only perceived missing component was a top-tier receiver, but that was inconsequential given the constructs of the offense.

Any quarterback would drool over that situation. The other mid-round hits were fortunate, too. Prescott was blessed with the league’s best offensive line and rushing attack, not to mention his loaded arsenal and his football think tank for a QB room. Cousins got to ease himself into a starting role, with three years both of occasional play and of tutelage under Sean McVay, before becoming the distributor to the likes of Jordan Reed, DeSean Jackson, and Jamison Crowder. Nick Foles had 10 weeks to get settled before seeing his first action, and he had all the support he needed in terms of line play and weapons. Jacoby Brissett was a Tom Brady pupil for a year.

This is where the re-draft experiment falls short. It fails to consider the peripheral factors that contribute to any given player’s performance. It’s impossible to separate the performance of the player from the situation in which they were placed as rookies. If Washington drafted Cousins second overall in 2012, instead of RG3, would he have been as successful without that precious developmental time? Would Prescott have been able to hit the ground running with the Rams, if he was taken first overall in 2016, in the same way he was able to with the Cowboys?

These questions are unanswerable. Their value, though, is in illuminating the fact that the preeminence of the development environment prevails throughout the entire draft. Those same central tenets of staff stability, surrounding talent, and system fit are absolutely critical to hitting on mid-round quarterbacks. Seattle, Washington, and Dallas nailed those mid-round picks because of their masterfully constructed development environments.

System Fit, System Fit, System Fit

The system fit component specifically stood out in the analysis of the middle rounds. In consideration of the systems from which these players came compared to the systems into which they were plugged, it’s easy to see why many of them were doomed from the start.

Most of the misses in this range were raw prospects who came from simplified spread systems that got the ball out early and often. Immediately upon entering an NFL building, these players needed to holistically reinvent their games from the basics, like footwork, to the advanced, like full-field progression ability, in order to adapt themselves to a professional system.

It's a process that many have tried, and many have failed, but not for the reason one would expect. The college-to-pro skillset adaptation process, in and of itself, is not insurmountable. It is the constraints the league places on practice time that are insurmountable.

The most important skills to be developed, the mental skills, come with live reps. The problem is that those priceless live reps go to the starters, whom the coaches need to get ready to win a ball game on Sunday. Thus, the majority of the “reps” the backups get are mental reps, and therein lies the importance of the system fit for middle round picks.

The better the system fit, the quicker the learning process. Since these players won't get the live reps needed to learn, finding close-as-possible fits to reduce the necessary learning time makes for much smoother transitions, and, thereby, longer careers. Of course, terminology will always be different, but identifying a player who has already done most of what he will be asked to do in the new system both from technical and schematic standpoints can do wonders for his transition.

When Nick Foles became the full-time starter in Philadelphia in 2013, the Eagles were running Chip Kelly’s no-huddle spread attack that, systematically, was akin to the system Foles operated for Sonny Dykes at Arizona. Although the play-callers may have differed philosophically in terms of their desired run/pass split, their systems were structurally and operationally similar.

The same goes for Jacoby Brissett, whose experience in Matt Canada’s system of multiplicity at N.C. State gave him exposure to the pro-style concepts he would be running both in New England and Indianapolis. Matt Barkley, who was pegged as a miss because of the quickness with which his drafted team moved on, has carved out a long career as a serviceable backup. His pro-style background from USC may have meshed better with the offenses he played in later than the Chip Kelly system into which he was drafted.

The track record in these rounds shows that, especially if drafting an envisioned backup, the right system fit is essential. Since a team is highly unlikely to adapt its system to fit the skillset of a backup, finding a prospect whose skill set fits the current offensive system, and, therefore, is very similar to that of the starter’s skillset, is the best course of action.

Leash Length

The list of misses is littered with examples of prospects who were system misfits once they got into the league. Further complicating matters was the fact that they were afforded very little time to fit themselves into their new system. This is the nature of the beast in the NFL. The mid-round quarterbacks don’t receive the same amount of developmental buy-in, the same leash, that early round quarterbacks do.

A cursory scan through the “Notes” column of the misses is an eyebrow-raising exercise. The majority of those players got two seasons, if that, with the teams that drafted them. Whether it be via trade or the waiver system, teams tended to move on from these passers not long after they drafted them. Particularly in the cases of players like Cardale Jones and Bryce Petty, who had NFL-starter tools but were multi-year projects, time was the ingredient needed more than any other.

Part of why this happens ties into the practice time point made earlier. There are only so many live reps to go around each week, and the majority, if not all, of them must be utilized to prepare the starters. The league’s practice system built for starter safety is not conducive to backup development.

So, these backups spend the majority of their rookie-year practice time running opposing teams’ offenses without repping in their own system, and by the time their second training camp comes around, they do not appear to have progressed. The front offices, doing their jobs to constantly upgrade the roster, will move on from them and roll the dice for a replacement either in the waiver system or in the following draft. And the cycle continues.

Now, recognizing mistakes and cutting losses is certainly prudent. That said, if even half of these players were given the same three-year-long leash that Kirk Cousins was given, the middle-round “hit list” may be a few names longer. It’s like moving on from a college quarterback after his redshirt freshman year, when the biggest strides are typically made during the third year in the program. The third- and fourth-round prospects need more developmental time and resources than their early-round peers, yet they typically receive much, much less.

It’s fair to say that the Not For Long principle applies to everyone; you must earn your keep. But this is the most difficult position to play in all of sports. Everything about it, from the preparation to the development process to the post-game film breakdown, takes more time. Because of that, a pinch of additional patience can be the difference between a hit and a miss.

Conclusion

Perhaps the biggest takeaway from this analysis is that only five of the 26 quarterbacks (excluding “jury’s out” designations) drafted between the third and fourth rounds in the last ten years were identified as hits. That’s to say, for each quarterback drafted within those parameters, the likelihood of a miss was 81 percent. Woof.

Again, many of both the hits and misses occur in the development process more so than the selection process. The quality of the development environment is the determining factor. For this reason, and in light of the fact that there isn’t a true development process for mid-round quarterbacks, it begs the question of whether looking for a long-term backup in the middle of the draft is a worthwhile endeavor.

If the development environment is of low quality, and if the system fit is incongruent, it’s not. The player will not have the time he needs to develop as envisioned under those circumstances. The ideal backups tend to be either unsuccessful starters (i.e., Gardner Minshew, Mitchell Trubisky) or former starters in their dotage (i.e., Joe Flacco, Andy Dalton), not developmental backups who reach their ceilings.

This research proposes that it is a better decision to outsource the backup in the free agent market or trade market than to attempt to grow one in your own garden. The relatively higher price to pay, either in the form of trade assets or a more expensive free agent contract, is the trade-off for the extremely low odds of a mid-round backup bet.