Analysis

12/9/22

8 min read

The Blitz Package That Terrorizes Modern NFL Offenses

If you watched the Cowboys beat the Colts last Sunday, you saw Colts’ quarterback Matt Ryan pressured by a furious pass rush. Sometimes it came off the edge. Sometimes it came from the inside. More than once, it came via the Double-A Gap blitz.

It’s a term not commonly known to NFL fans, but it was to Matt Ryan last weekend.

The Double-A Gap Blitz is a defensive maneuver where two defenders blitz through gaps between the center and the two guards – areas referred to as A gaps. You saw examples of it in play twice in the second quarter of the Cowboys-Colts game, and in both instances it worked to perfection.

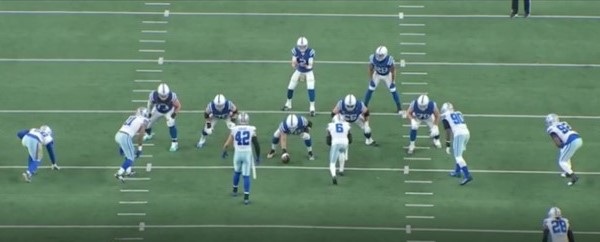

The first occurred early in the period, when Dallas safety Donovan Wilson and linebacker Anthony Barr lined up on opposite sides of center Ryan Kelly on a third-and-5 at the Colts’ 25.

When the ball was snapped. Kelly immediately turned to his right to pick up Barr.

But that left Wilson, lined up to Kelly’s left, free to rush the quarterback unimpeded—and he did. He shot through the gap and sacked Ryan.

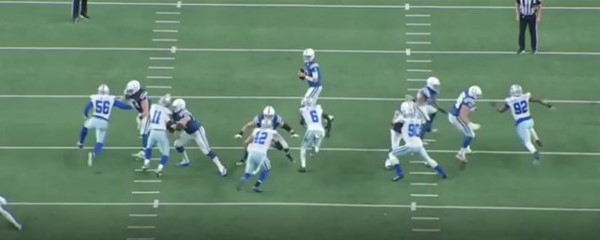

Later in the second quarter, with the Colts sitting on a third and 5 at the Dallas 43 yard line, linebacker Micah Parsons and safety Jayron Kearse tried another Double A Gap Blitz. Only this time the Colts’ offensive line shifted right to block each of them before they could break the protection.

That left Barr, lined up in the B gap between left guard Quenton Nelson and left tackle Bernhard Raimaan, unblocked; and you can imagine what happened next.

Barr breezed past running back Jonathan Taylor, lined up to Ryan’s right, and dropped the beleaguered quarterback for another sack.

It was the beginning of a long evening for Ryan and the Colts. Ryan was sacked three times, pressured seven times, threw three interceptions and fumbled once. The result? The Colts were outscored 33-0 in the fourth quarter and suffered a 54-19 defeat. Matt Ryan learned a hard lesson that day. The Double-A Gap Blitz can be effective.

But how did the Double-A Gap Blitz get it's start? It goes back to my days in Dallas, when I was working as the defensive coordinator for Bill Parcells. One day Bill came up to me in practice and said, “Hey, do you ever change this one blitz?’’ I didn’t know what he was talking about.

“Well, If the center’s going this way,” he said, pointing in one direction,” do you ever replace the guy he’s supposed to block with another defender and let him rush?” I had never heard of that. So I told him, “No, we haven’t done that." But when I went to Cincinnati several years later as the defensive coordinator, I sat in a room with head coach Marvin Lewis and Paul Guenther—who was an ex-offensive coach and knew protections—and we talked about how we could get to a running back quickly; just as Barr did with the Colts’ Taylor.

We already had our blitzes in, so we said, “Let’s walk both linebackers up in the A gaps and see what happens.” What happened was that the center would point one way or the other, which told us just what we wanted to know. If he pointed left, then our left linebacker could come through the gap to his right and get right to the running back. Remember, the thrust of this package was to get one linebacker on a running back and the other into coverage. Once the offensive line showed where it was going, we knew what to do.

There were all sorts of variations of this blitz. Sometimes we would walk up the free safety and put him to the weak side of the formation. Then we had the nickel back on the other side. We didn’t want to tip the blitz. We wanted an even triangle. The safety who was in the middle of the field–that would be the strong safety–would line up directly over the ball, with the weak safety on one side and the nickel back on the other.

When I was the head coach in Minnesota, it got to the point where we’d change the blitz sometimes based on the offensive lines we faced. I had seen a number of teams try to emulate us on defense by having defenders in the A gap read the center after the snap. But that’s not what we did. We just listened to what the offensive line was telling us because it was quicker.

Now, I know what you’re thinking: Listening to the offensive line? Correct. If, say, the center yelled out “Rip,” that would tell us he was going to his right. If the quarterback called out, “The Mike is 55,” as he stood ready to take the snap, it told the center to look for the middle linebacker.

There were always clues. But that doesn’t mean they always worked.

When you’re playing Tom Brady, for instance, he knows where he has to get the ball. He’s going to get it out quickly, and he’s not going to take the sack. He’s smart enough to know where to go as soon as the ball is snapped. So we had to plan a different blitz when we played him a couple of years ago.

With a scrambling quarterback, it’s different because I didn’t want the end to drop into coverage. If the quarterback gets out of pocket and starts to run, it could be bad news–as you’ve seen when Patrick Mahomes, Lamar Jackson or Justin Fields get loose. So we tried to keep them guessing by sometimes having both ends rush.

Over the years the Double-A Gap Blitz evolved. Initially, it was a nickel back and a linebacker or safety and an additional linebacker that we brought. But it became so sophisticated that we’d say, “Let’s back down and go pick the center or go pick the guard and run a loop with the defensive end who wasn’t dropping.”

Sometimes we’d just bring the nickel back and play Cover-2. When the two tackles would go to three techniques, we’d walk our linebackers up in the A gaps and have that exact same look. But we could bring a linebacker or whoever was going to be on the running back and line him up there, drop him out and play some form of Three Deep or Two Deep coverage.

I remember using it in Cincinnati once when we played Minnesota. On the first third down of the game it caused a red-zone fumble. Later, when I went to Minnesota, the first time we used it, Harrison Smith intercepted the ball and returned it for a touchdown.

What we’d try to do early in games is what we called “Split Bluff,” where we’d bring the linebackers up, see what our opponent was going to do, and then drop everybody out on the snap to figure out how they were going to play us that day.

After a while offenses starting saying, “OK, how are we going to adjust?” The first thing we saw was that they brought extra guys inside to protect, usually a tight end. Then they started moving backs into the A gap to narrow the space between the guard and center, which made us check to a two-man coverage defense. But that actually made it easier for us. It told us which way the center and back were going.

Eventually, it got to the point where we’d change coverages based on where the tight end would go. One time when we played the Giants, as soon as we lined up guys in the A gap they motioned the tight end to the other side and ran a toss sweep. It worked, which meant we had to adjust. The next time we saw them motion the tight end, we told our guys to back out and play normal.

There was a lot of cat and mouse going on.

When we first talked about this, the whole idea was to get to a running back as fast as we could. We knew the fastest way to get in the quarterback’s lap was to get in his face immediately. So when you have a guy like Barr, who’s 6-4 or 6-5, and he’s on a small running back trying to protect a quarterback who’s 6-2, it becomes pretty effective.

Now, of course, offenses seem to feel more comfortable vs. the blitz than they did. Where once they were trying to block a bunch of hybrid guys, everybody now lines people up and down the line of scrimmage. It’s kind of like Buddy Ryan’s “46” defense in Chicago where they had all these players up near the line of scrimmage. Because of the looks we’re getting from offenses today, when you get to third downs everyone has hybrid guys up on the line trying to do what we did with linebackers in A gaps – create confusion for the offenses in protections and misery for the quarterbacks.

Does it work? I‘ll let Matt Ryan answer.

As told to Clark Judge