Analysis

8/4/23

9 min read

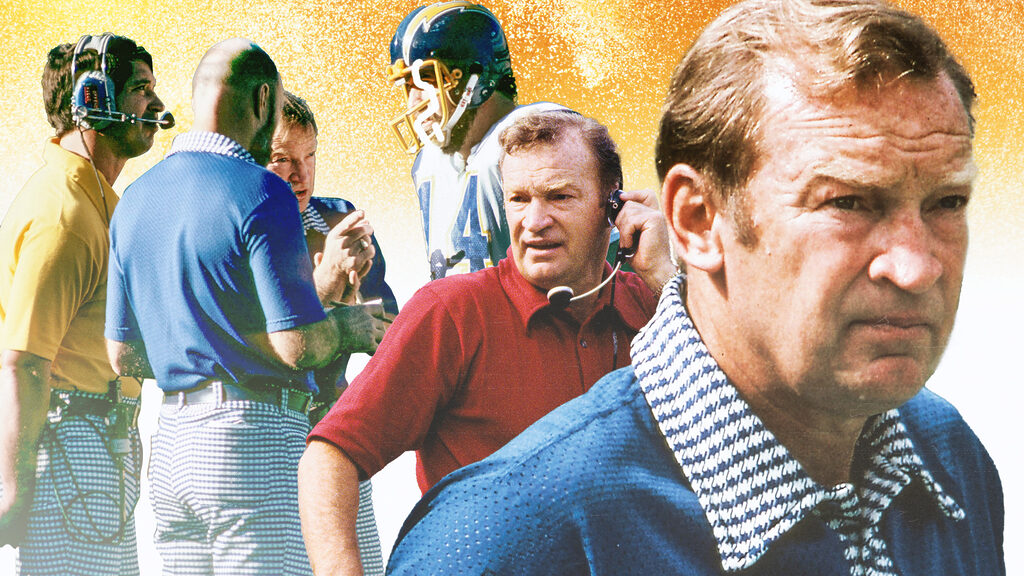

How Don Coryell Changed Football Offenses Forever

Thirty years after Don Coryell presented him for induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, Dan Fouts will complete the circle Saturday and do the same for his late coach and friend.

“You wouldn’t be talking to me right now if not for Don,’’ Fouts said earlier this week. “So many things in my life and career can be traced back to that day Don walked into the room in San Diego in 1978.

“When he was hired, I couldn’t imagine it would have the impact it did. But I certainly was excited when he took over because I knew so much about him and his offense from what he had done at San Diego State and in St. Louis [with the Cardinals].’’

What Coryell did at San Diego State and then with the Cardinals was change the way football was played. The man who helped develop the power-I for John McKay as an assistant at Southern Cal ditched the game’s conservative 3-yards-and-a-cloud-of-dust approach and dragged the rest of the football world kicking and screaming into a new era where the pass became the thing.

Air Coryell Takes Flight

The Chargers offense became known as Air Coryell, and rightfully so. In Coryell’s nine seasons as the team’s head coach, the Chargers led the league in passing yards seven times and total offense five times. During his first four years, the Chargers finished second, fourth, first and first in scoring.

In Fouts’ first five seasons with the Chargers, before Coryell arrived, he had a 12-30-1 record as a starter and threw just 34 touchdown passes. Canton was a pipe dream for him at that point.

Then Coryell arrived, and everything changed. Fouts went to six Pro Bowls in nine seasons. He’s the only quarterback in history to lead the league in passing yards for four straight years (1979-82). In 121 games with Coryell, Fouts threw for 32,865 yards – 271.6 yards per game – and 210 touchdowns.

“He changed the game on both sides of the ball,’’ Fouts said. “You can see how the game really changed once he took over in San Diego. The numbers that his offense put up and the gradual increase (in passing numbers) with other teams around the league.

“Kellen Winslow said it best when he said look at the TV ratings and the TV contracts and how they exploded in the '80s and '90s and 2000s. Look at what happened with player salaries. Interest in the game is worldwide. When did it all start? When Don took over the Chargers, that’s when.’’

Finally Called to the Hall

Yet, it’s taken Coryell, who passed away in 2010 at 85, a long time to get his invitation to Canton. Why? Well, football coaches are ultimately measured by wins and losses and championships. Coryell is 41st in career NFL wins with 111. Norv Turner has 114. John Fox has 133. Nobody ever will be mentioning Turner and Fox as candidates for Canton.

Coryell is the only one of the 21 Hall of Fame coaches since 1970 not to have ever won at least one conference or league championship.

A seven-time finalist, Coryell’s coaching record clearly was why he kept coming up short in the Hall of Fame voting. Earlier this year, the Hall of Fame approved a change to its by-laws, which combined coaches and contributors into one category. With selectors looking at all of Coryell’s contributions to the game and his record, he got the necessary votes.

“The focus on the contribution side is what helped Don get in,’’ said Fouts, one of the 50 selectors for the Hall of Fame. “It swayed many of the voters who were against him. They no longer had an argument.’’

Coryell’s innovations are many. Some things he has been credited with introducing to the game include pre-snap motion, the single-back alignment, running back screens, option routes and the three-digit numbering system for the passing game.

The impressive list of assistants who worked for and learned from Coryell included Hall of Famers John Madden and Joe Gibbs, as well as Norv Turner, Ernie Zampese, Rod Dowhower and Al Saunders.

“When he first got to San Diego State (in 1961), Don ran the Power-I,’’ said another Hall of Fame coach, Dick Vermeil. “I was a junior college coach and went to a football clinic, Don was the featured speaker, and it was all about the Power-I.

“I mean, they ran the hell out of the ball at San Diego State. But his offense gradually moved to the wide-open offense with movement, with spread formations and using the tight end in the passing game and those types of things.’’

West Coast Offense Precursor

“He expanded the passing game in so many ways,’’ said Hall of Fame GM Bill Polian, an analyst for The 33rd Team. “Coryell expanded on what Sid Gillman had done in San Diego prior to him, and he expanded on what Tom Landry had done with the Cowboys and what Allie Sherman had done with the Giants.

“He created a passing game that would become the basis of the West Coast Offense – the timing, the route tree, all of that. That’s all Don Coryell. And then the emphasis on the passing game, in terms of tactics and strategy, was all him. He was the godfather of the modern tactical, strategic passing game where the passing is the dominant force.’’

San Diego State had a 1-6-1 record and averaged fewer than seven points a game the year before Coryell took the job there. He turned the program around, first with the Power-I, then with the pass. In 12 seasons, he was 104-19-2.

“I just decided, hell, you can’t just go out and run the ball against better teams,’’ Coryell once said. “You’ve got to mix it up. You’ve got to throw the damn ball if you’re going to beat better teams.’’

His success and his innovative offense caught the eye of the bad-awful St. Louis Cardinals in 1973. He was the NFL’s coach of the year in his second year there as the Cardinals went 10-4 and made the playoffs for the first time in 26 years.

They won 11 games in ’75 and 10 in ’76. But when they slipped to 7-7 in ’77, the Cardinals, who historically have had a knack for doing the dumbest thing possible, fired Coryell and replaced him with former University of Oklahoma coach Bud Wilkinson. Wilkinson, who had been out of coaching for 15 years when the Cardinals hired him, didn’t last two seasons.

The Cardinals’ stupidity worked out well for the Chargers, who fired Tommy Prothro three games into the ’78 season and replaced him with Coryell.

Opened the Game Up

Their passing game was unstoppable, with Fouts throwing to the game-breaking likes of Charlie Joiner, Kellen Winslow, John Jefferson and Wes Chandler.

“He found a way, with this incredible Hall of Fame quarterback, to spread the ball around, to do it in a way that really gave defenses difficulty and allowed him to take advantage of the personnel he had,’’ Polian said.

“It was the same thing that Bill (Walsh) did in San Francisco in a slightly different way. But the timing of the West Coast offense is all based on the stuff that Don did.’’

Air Coryell was helped by two rule changes implemented in ‘78. The first was the Blount rule, named after the Pittsburgh Steelers’ physical cornerback, Mel Blount. The rule change prevented defensive players from jamming and manhandling receivers beyond 5 yards of the line of scrimmage. Previously, there was no limit.

The other rule liberalized pass-blocking, allowing offensive linemen to extend their arms and use their open hands while pass-blocking.

“Those two things, smart coaches like Don recognized that it gave them the opportunity to open the game up,’’ Polian said. "Those two rules enabled the pass game to thrive and gave the offense a decided advantage over the defense.’’

Elevated Tight Ends

A year later, in 1979, the Chargers selected Winslow, a freakish 6-foot-5, 250-pound tight end out of the University of Missouri, in the first round of the draft. Winslow gave Coryell and Fouts a receiver who would become a matchup nightmare for defenses.

“Don always wanted to keep trying things,’’ Fouts said. “He wasn’t afraid to ask for input from his coaches and players. He wasn’t afraid to ask himself, what if we do this or that? What if we take Winslow and put him in motion and create a mismatch?’’

In 1980-81, Winslow became the first tight end to lead the NFL in receptions in consecutive seasons.

“While it would seem obvious later on, not a lot of people realized Winslow had that kind of talent, to begin with,’’ Polian said. “Back then, tight ends were just that – tight ends. In those days, 250-pound guys operated mostly in short areas.

“Aaron Thomas was the forerunner to Winslow as the athletic tight end with Allie Sherman and the Giants. But Kellen came into the league and had more talent, speed, dexterity and flexibility than Thomas, and Don said he’s a weapon.

“Instead of using him as a short or intermediate route runner, he was the forerunner to Gronk (Rob Gronkowski), running seam routes, deep routes and deep corners and all that kind of stuff. He was a matchup nightmare.’’

Coryell not only liked to throw the ball. He liked to throw it deep. Of course, having receivers like Jefferson, Chandler and Joiner (who went into the Hall of Fame in 1996, three years after Fouts) helped.

Joiner averaged 16.2 yards per catch in his career. Chandler averaged 16.0, including a career-best 21.1 in 1982. Jefferson averaged 17.7 in his three seasons in San Diego before being traded to Green Bay in 1981 after leading the league in receiving yards.

“What it did was put defenses on alert,’’ Fouts said of the Chargers’ penchant for the deep ball. “It loosened them up a bit. If we had the ball backed up on our own 5, Don’s approach was that’s 95 yards the defense has to cover. It gave us such confidence that if it’s there, we’re going to take it. And if we take it, it’s going to be good. Even if we don’t complete a long bomb, it messes with their mind.’’

Paul Domowitch covered the Eagles and the NFL for the Philadelphia Daily News and Philadelphia Inquirer for four decades. You can follow him on Twitter at @pdomo.