Analysis

1/20/22

4 min read

What is Dead Money?

The salary cap is one of the most misunderstood areas of football, and the term Dead money is often misinterpreted in regard to calculating a salary cap charge. This brief explanation will define what the term means, how it is calculated, and its potential implications.

What is Dead Money?

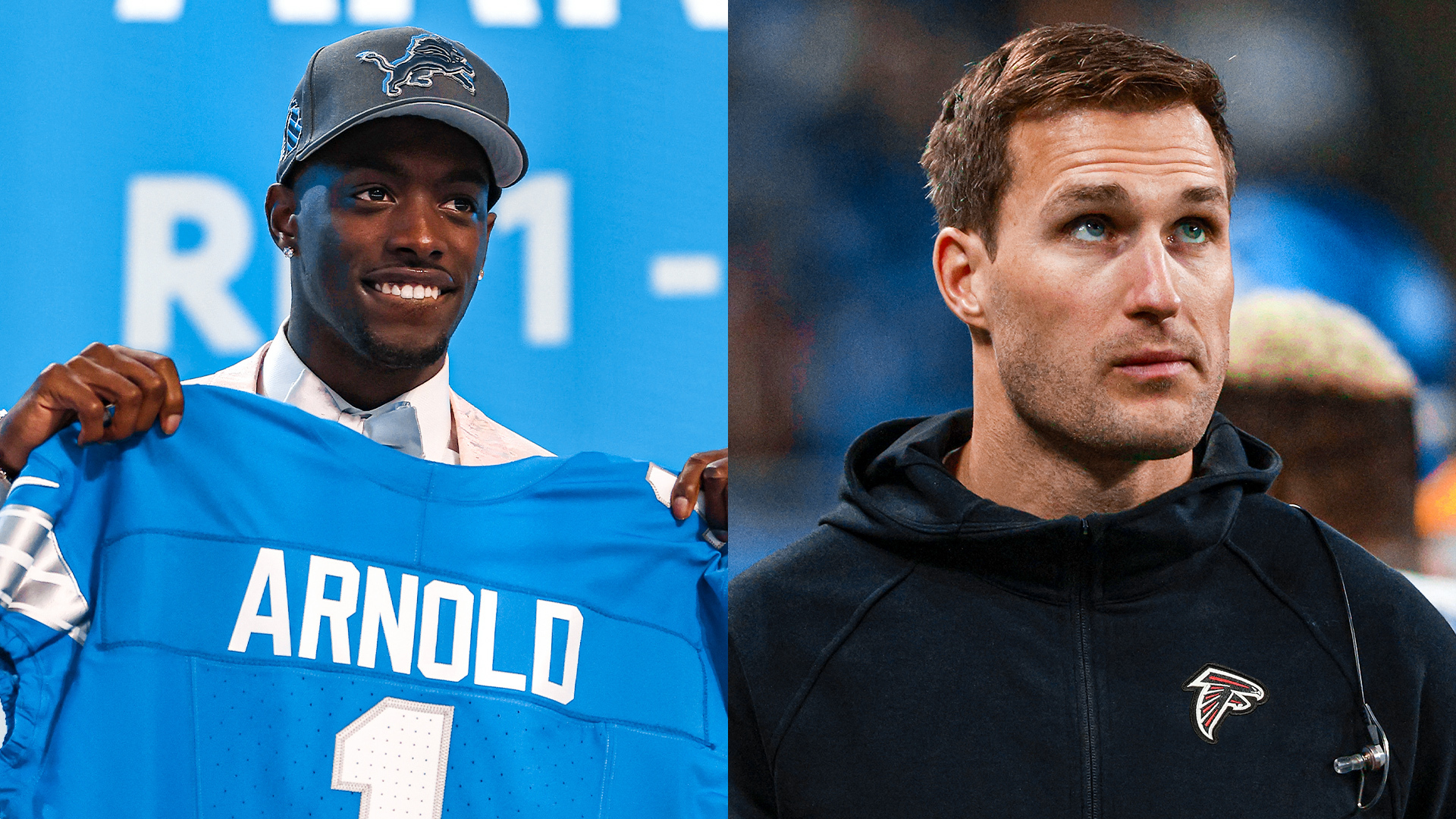

Dead money is a salary cap charge for a player that is no longer on a team’s roster. The charge continues to count even though the contract of the player has been terminated or traded. Fully guaranteed money, prorated bonuses, termination pay, and injury settlements can all be included in dead money. Prorated bonuses are the most common form. Teams can spread finance charges over up to five years using prorated bonuses, such as signing bonuses, with a percentage of the bonus accounting against the cap in each year.

Proration becomes an issue when the player does not play to their expected level of play, and the team wants to move on. Per the Collective Bargaining Agreement, future charges accelerate into a current season’s cap if a player does not fulfill the entire term of his contract. Dead money can critically impact salary cap dollars a team can allocate to contributing players, therefore greatly affecting their ability to compete.

For example, if a player signs a 4-year contract with a $12 million signing bonus, the signing bonus would be prorated into $3 million installments each season for salary cap purposes. If the player underperforms in his first season, the team can terminate his contract early. However, if the team terminates the contract after the first year, the player’s dead money charge would be $9 million and would accelerate into a current season’s salary cap.

How is It Calculated?

Dead money is calculated by adding all remaining prorated charges for the current year and future years of a contract. Salary cap managers must conduct a cost benefit analysis of dead money when deciding whether to terminate a player contract. Cap savings refer to the result of terminating or trading a player’s contract. This value is important for dead money valuation because teams may decide to keep a player even though he is underperforming, because it would cost them more salary cap dollars to terminate his contract early.

When dead money is greater than cap savings, it is a strong player contract and practically guarantees their roster spot. However, it is not a true guarantee, as teams may still release a player despite the dead money charge if the cash savings are enough. Teams may decide to take on large dead money charges to avoid overpaying players who are not contributing enough.

June 1st is an important date for salary cap purposes in the NFL. After June 1st, future years’ prorated money no longer accelerates into the current league year. Instead, it accelerates into the following season. Only current year prorated bonuses count towards dead money for the current year. This way, a team that did not have the cap space to release a player, can wait until after June 1st to do so.

Using the earlier player contract example of 4 years/ $12 million signing bonus, in a post June 1st termination after the first contract year, the dead money charge for the current year would be $3 million, and the following season it would be $6 million. NFL teams can designate up to two players a year as post June 1st cuts for salary cap purposes. The June 1st rule does not apply to fully guaranteed salaries for skill, injury, and cap; meaning all guaranteed money accelerates into the current year even if the player is released after June 1st.

Dead money charges can greatly impact a team’s ability to compete in the NFL. It is one of the most important aspects of player contract negotiations as well as a team’s roster flexibility.