Analysis

12/21/22

10 min read

How Teams, Officials Failed to Be 'Critically Efficient' in NFL Week 15

During our time in Indianapolis, Tony Dungy would often speak to our team about the difference in the NFL between perception and reality.

He would use video snippets of broadcasters extolling our opponents as “unbeatable” and “the greatest of all time.” Dungy then would put on a reel of tape showing that same player and those same opponents making mental mistakes, turning the ball over and committing penalties, all of which contribute to losing.

The moral of the story is we are all human. No one is unbeatable. We all make mistakes and mistakes lead to losses. The team that makes the fewest mistakes usually wins.

Dungy urged our players to live in a world of reality, to ignore perception, and, at crunch time, fall back upon the tried and true fundamentals we had practiced since OTAs. Our mantra was, “Do the ordinary in an extraordinary way.”

There is a corollary to Dungy’s point on perception versus reality. The purveyors of perception start with the premise the winner of a given game should “dominate” statistically and on the scoreboard. If not, “Something is wrong.” The loser of that game is either in “dire straits,” or if the losing squad is a marquee team, it “has serious cause for concern.”

The reality is captured accurately in this quote from the late, great Joe Paterno: “You’re never as good as you look when you win and never as bad as you look when you lose.”

Another key component of football reality was an axiom I read more than a half-century ago from the legendary University of Texas coach Darrell Royal that is still true today at all levels of football.

“In every game, there are five or six plays that decide the outcome. The problem is you can’t predict when or how they will occur. Therefore, you must design, coach and practice every possible situation to be prepared when the critical situation occurs.”

Bill Belichick calls this situational football. With the Colts, we called it critical efficiency. Critical efficiency means when one of these game-changing plays occurs and you, as a coach, player or official, are a part of it, you must perform at the highest level of your ability.

To do that, you must be prepared both technically and tactically. You must be mentally ready and execute the required assignment in a winning fashion. You must do this consistently. Bill Walsh called it the "Standard Performance." It is graded every week. Coaches and players were held accountable. If an individual was not critically efficient consistently, he wouldn’t keep his job.

Winning does not occur by accident nor often by the heroics of individual players. It is a byproduct of intense mental, physical and emotional preparation that allows a person to meet the moment and be critically efficient when those game-changing situations arise.

Critical Efficiency's Importance in Week 15's Crazy Games

There were many games with major playoff implications last weekend. There were numerous situations where coaches, players and officials had to be critically efficient. Let’s examine a handful. Some will be obvious and some may be surprising. This, by the way, is not second-guessing. It is the examination of alternative strategies and actions that might have led to a different result.

Colts vs. Vikings

We’ll start with the wild Indianapolis-Minnesota game. The Colts were up at the half, 33-0, without scoring an offensive touchdown. Minnesota had stumbled, bumbled and slept-walked with only its red-zone defense resembling a playoff team. Late in the third quarter, the Vikings came alive.

They were aided by a plethora of Indianapolis' mistakes and an officiating error, not made by an on-field official, but by a rule created by the NFL membership without input from the Competition Committee. That rule makes it a personal foul if “a player lowers his head and makes forcible contact with his helmet against an opponent.”

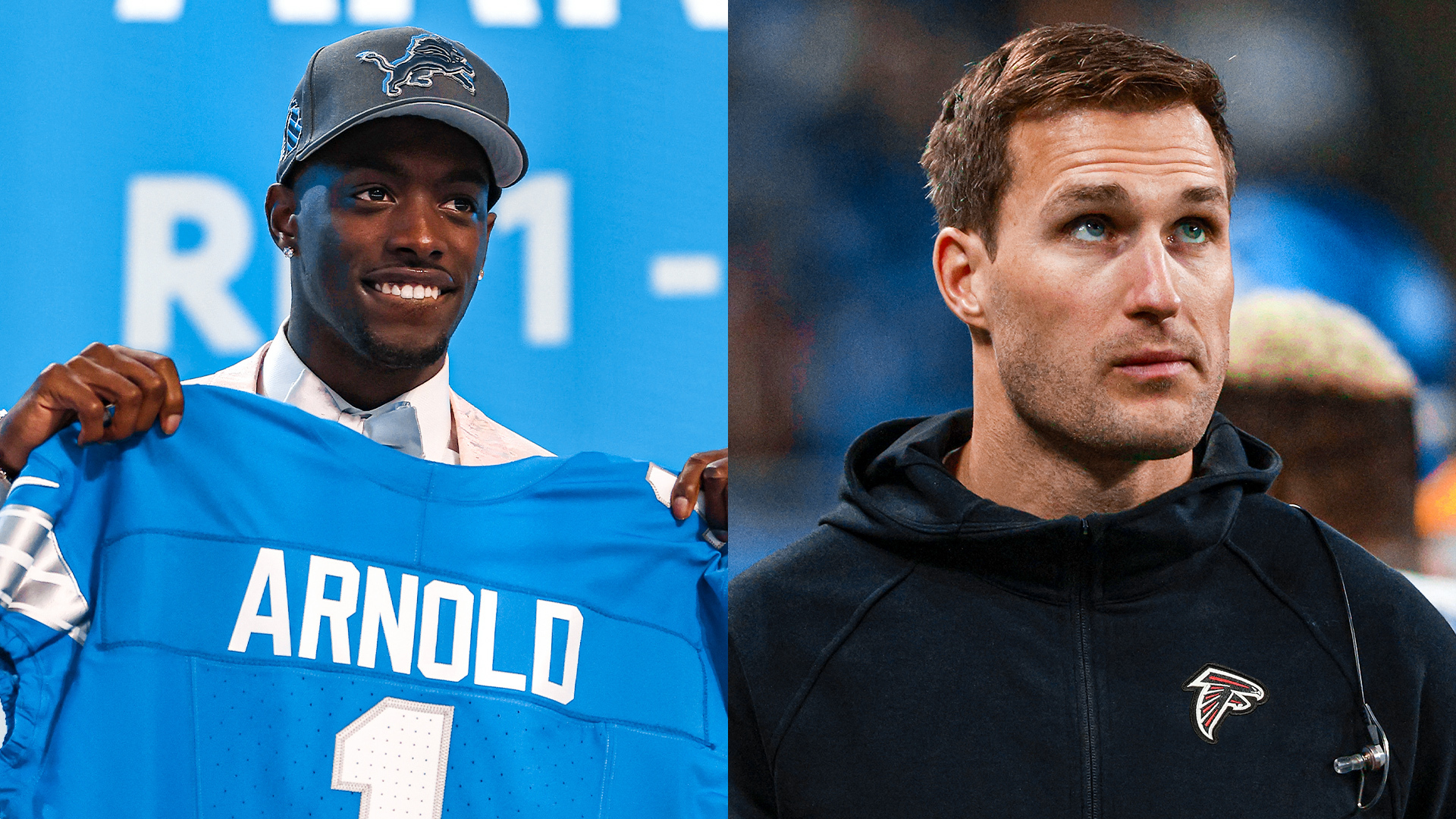

During the Vikings’ frantic comeback attempt in the fourth quarter, Kirk Cousins completed a pass to Justin Jefferson. Jefferson ran down the sideline and, while in bounds, was contacted by safety Rodney Thomas in an attempt to knock Jefferson out of bounds. Thomas hit Jefferson hard with his shoulder. There appeared to be slight incidental contact with Thomas’ helmet. The official threw a flag for unnecessary roughness.

Because there was no explanation, I can only assume it was for hitting with a lowered helmet. However, after watching the play in a real-time replay that was not the case. Indianapolis was penalized a precious 15 yards that led to a Vikings score. At a time when critical efficiency was necessary, the official failed to meet the moment.

He, however, is not to blame. The fault lies with the league for creating a rule whereby the coaches, players and officials can’t be right. This rule is poorly written. The proper technique to avoid a foul cannot be coached, and it cannot be consistently officiated.

As a result, it is randomly called. In reality, it can only be officiated by slow-motion replay. Since it is not a reviewable play, on the one hand, it is inherently unjust, and on the other, it is impossible for the officials to be consistent.

Now to an Indianapolis coaching error at the game's most critical moment. Late in regulation, with fourth down and a foot to go, the Colts called for a quarterback sneak. If they get the first down, the game is virtually over since the Vikings had no timeouts remaining.

Instead of putting two offensive linemen in the backfield to legally push quarterback Matt Ryan forward, he was left on his own. There was a stalemate at the line of scrimmage and no push for Ryan from behind. The result was a turnover on downs, followed by a 64-yard screen pass for a touchdown to Vikings running back Dalvin Cook that put the game into overtime.

It wasn’t the call on fourth down that was wrong. It was the Colts’ offensive coaching staff not being critically efficient. They did not take advantage of the “pushing the runner” rule to give Ryan the best chance to gain six inches, and their team to win the game.

Patriots vs. Raiders

We’ll now turn to the Raiders-Patriots game. With 37 seconds left in regulation and Las Vegas behind by a touchdown, Raider quarterback Derek Carr launched a go route to wide receiver Keelan Cole. He was single-covered. The Patriots’ corner was critically inefficient since he did not prevent Cole from making the touchdown catch.

At that point, replay stepped in and began an interminably long review. Despite numerous views that the fictional “50 guys in a bar” would have found the receiver to be out of bounds, the catch was upheld and the game was headed for overtime. So much for critical efficiency in replay. As Lee Corso would say, “Not so fast.”

After a good kickoff return, the Patriots had one last play prior to the expiration of regulation. The question has been asked, “Why not have quarterback Mac Jones kneel and let time expire?” That is perfectly appropriate.

The Patriots instead chose to run a draw play with their best player, Rhamondre Stevenson. That is perfectly OK as well. If the draw caught the Raiders off-guard, a TD run would've given New England the win. In my view, there is a small risk of a fumble with a huge reward if the surprise works.

Now comes player error on a monumental scale. First, Jones, in the huddle, should have reminded Stevenson to secure the ball, and if he met with any resistance of any kind, he should go to the ground. The game was tied. Stevenson going down with the ball would have sent it to overtime. There was no need for a last-ditch, do-or-die lateral play. If Jones did provide that reminder, Stevenson didn’t get the message.

At a time when ordinary, garden-variety common sense and reliance on fundamentals were required, Stevenson went off the air. He lateraled the ball back to wide receiver Jakobi Meyers. Meyers didn’t want it, so he lateraled it farther backward to Mac Jones. That lateral was intercepted by Raiders' defensive end Chandler Jones, who ran it into the end zone for a touchdown in one of the most unlikely victories in NFL history.

Knowing Belichick’s coaching acumen, I bet this desperate end-of-game scenario was covered at some point in practice. The players clearly didn’t learn that lesson, and it cost the Patriots the game. This is a failure in critical efficiency and, worse, an unforced error.

Giants vs. Commanders

Another game with a failure of critical efficiency was the Giants at the Commanders, which was an important game for playoff positioning. Late in the game, with the Commanders trailing by eight points, there were multiple plays that highlighted the need for critical efficiency on the part of players and officials.

The first was an illegal formation call against wide receiver Terry McLaurin that negated a Washington touchdown. McLaurin was aligned 15 yards from the play and had no effect on it. He was the outside receiver in a slot formation and initially aligned incorrectly. After communicating with the official, McLaurin corrected himself.

Dean Blandino, an analyst for The 33rd Team and former NFL officiating director, viewed the play and explained there was no advantage gained by Washington no matter where McLaurin was before the snap. Blandino explained that as long as there was “as little as a blade of grass” between McLaurin and the receiver inside him, there was no foul.

The second play was on fourth-and-goal, following the enforcement of yardage on the McLaurin play. Washington quarterback Taylor Heinicke rolled to his left and threw to Curtis Samuel in the end zone. Samuel was covered, one-on-one, by Giants cornerback Darnay Holmes with no help.

Holmes manhandled Samuel long before the ball arrived. The replay (in real time, not slow motion) clearly showed defensive pass interference. Blandino, along with the rest of the football world, believes it was clearly DPI. This play is the definition of critical efficiency. Heinicke and Samuel did their job. The official did not.

Unlike players, however, the official will keep his job and move on to the next game. Given the circumstances, both these badly missed calls are a black eye for the NFL.

In the end, efficiency and poise in a balanced league will carry the day. That’s the secret sauce that propels teams to victory in the NFL.

As told to Vic Carucci