Analysis

11/25/22

9 min read

How NFL Coaches Can Help Players Flip Switch, Turn Light On

One of the most important lessons I learned about athletes, which I carried into my coaching career, is that knowledge is confidence and confidence lets you play fast.

I learned that 60-something years ago, as a senior playing basketball for River Dell High School in Oradell, N.J. I call it “turning on the light for a player.” The person who did that for me was Mickey Corcoran, who coached our basketball team there and who was like a second father and highly influential on me eventually coaching football.

We were in the state tournament. There were eight seconds to go in the game and we were down one and setting up an out-of-bounds play past half-court on the other team’s side. We huddled up and Mickey said, “Bill, I’m gonna get you the ball at the foul line extended with your back to the basket. When we do, there are going to be about six seconds to go as you take possession.”

That was all he said, but it was the greatest piece of coaching that I ever got because he solved all my problems for me. He told me what position I was going to be in, where I was going to get the ball and how I was physically going to be when I got it. I knew what was going to happen. I wasn’t worried about how I was going to do anything. Now, I knew my job was to score, but he drew it up and we executed it.

It was a vivid piece of instruction that taught me, as a coach, you’re always looking for vehicles to solve the problems that a player’s having. You have to solve the problems for the player or else the player can’t play at the speed and the ability that he has because he’s too busy thinking about what to do.

I can remember some key instances while coaching the Giants where I helped turn that light on. No matter how meticulous and how thorough your game plan is, sometimes you just can’t get the player to do what you want him to do. The part for me that was difficult was finding the right brief words that would allow the player to at least attempt to solve the problem.

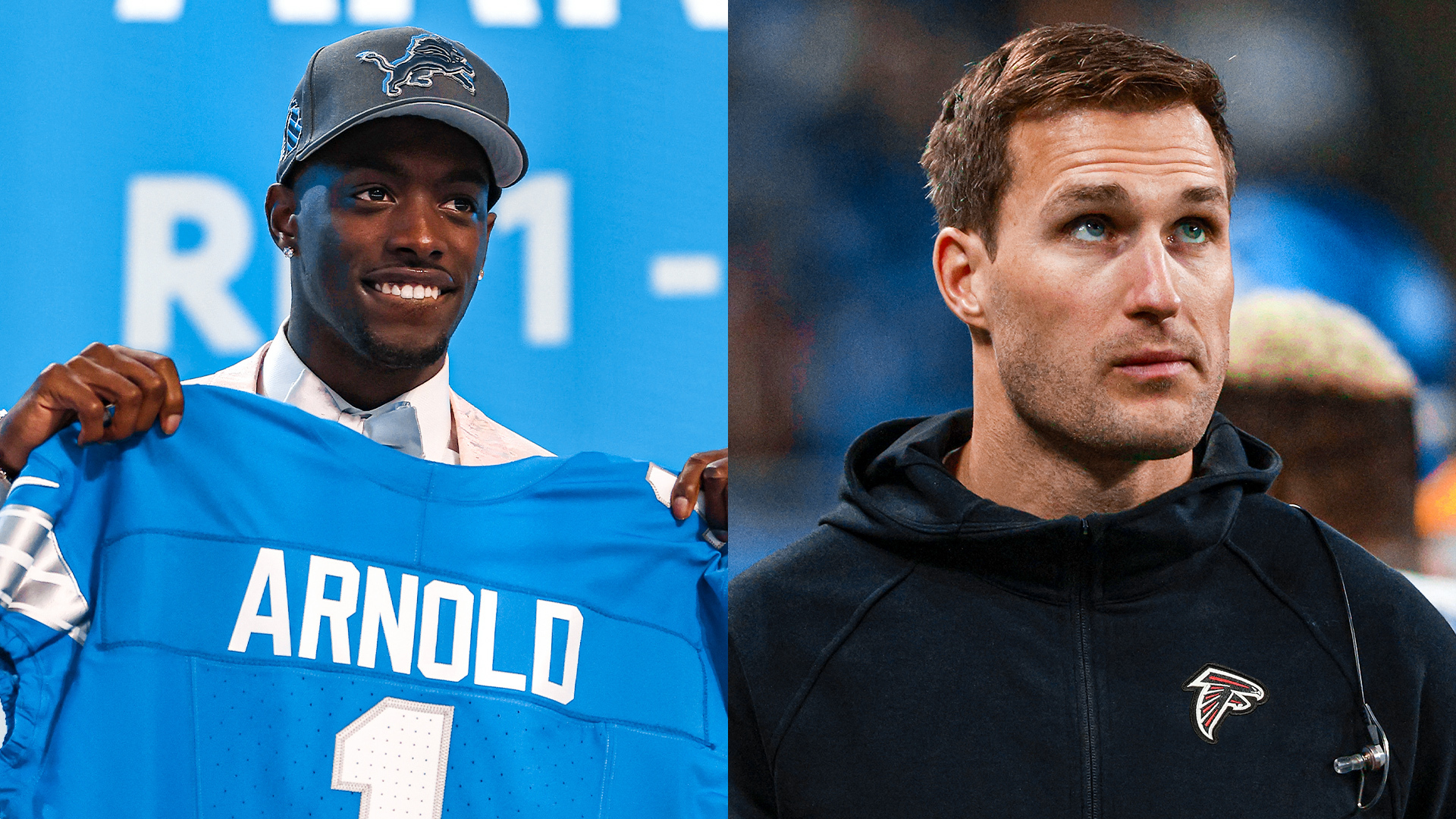

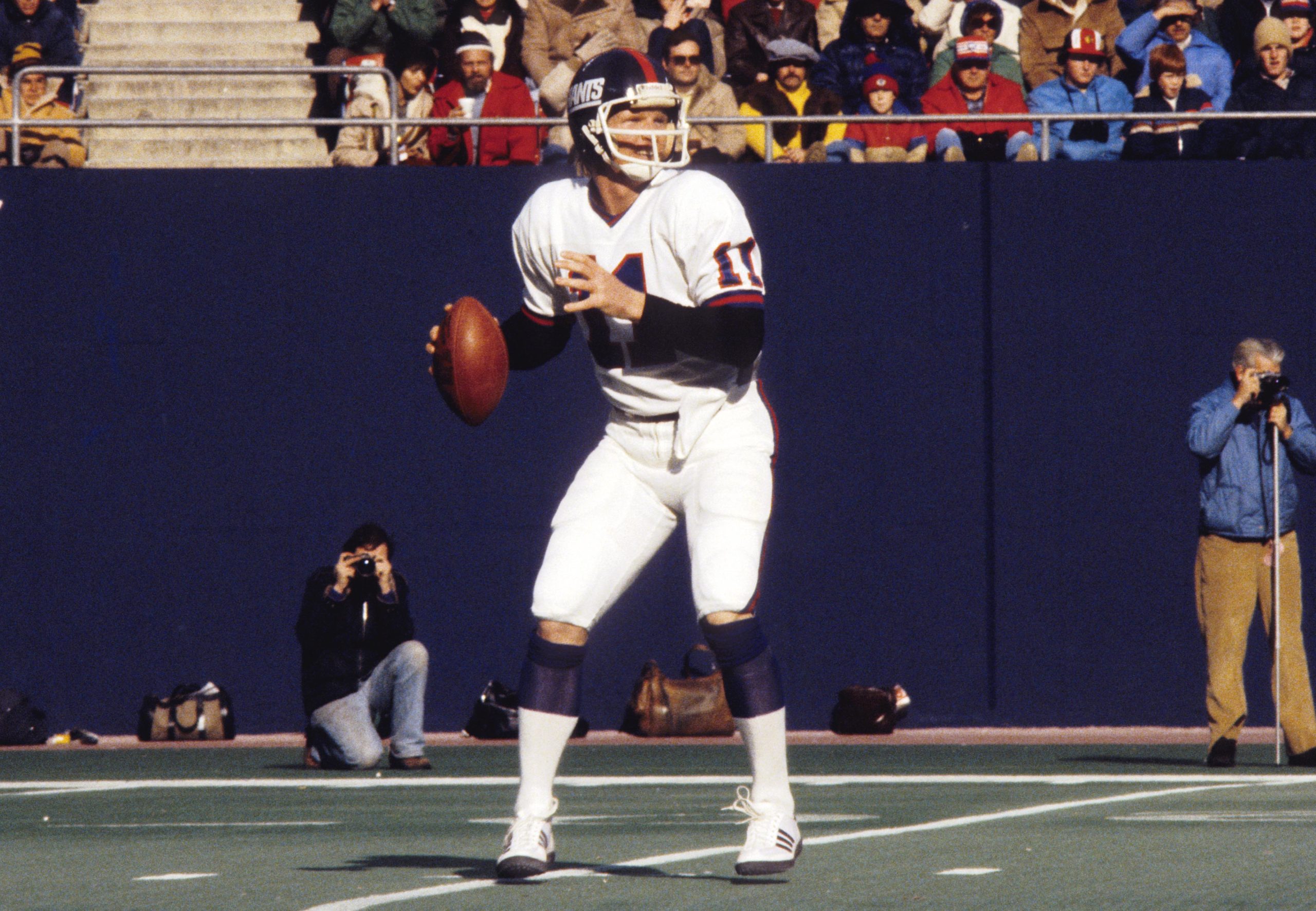

In 1984, we were 8-5 and playing the Chiefs in New York. It was our first shot at the playoffs. Kansas City had two very good defensive backs at the time. Albert Lewis was a left corner. He was almost 6-foot-4 and had been a safety in college. The Chiefs also had a very good free safety named Deron Cherry. We knew they were pretty good ball hawkers.

Now as the game went on, we were calling plays and Phil Simms would not throw the ball to the guy that we thought was open. So, I talked to my offensive coordinator, Ron Erhardt, on the headphone.

“Ron! Ron! What happened to that out-cut there?”

“Bill, it’s open. He won’t throw it.”

When Simms came back to the bench, I said, “Phil, what about the out?”

“Oh, Bill, that Lewis, he was sitting right there. If I had thrown that, he would have been able to make a play on the ball.”

Later on in the game, we called a seam route. Once again, Phil wouldn’t throw the ball. Once again, I got on the headset to Erhardt.

“Bill, it’s wide open,” Ron said. “He won’t throw it.”

Simms came back to the sideline and I said, “Phil, what about that seam?”

“That Deron Cherry, he was looking right at me. If I threw it over there, he was gonna' make a play on it.”

There were about nine minutes left in the game and Kansas City had just gone ahead, 27-14. We had the ball on our own 10-yard line and there was a television timeout. I called Simms over and I said, “You know, Phil, I’m gonna' tell you something now that I never told you before, but I want you to do exactly what I tell you to do.”

“Okay, okay,” he said.

I told him we were going to get into a formation we called “Eight Slot Out.” That put a slot receiver on the left, a tight end on the right and our halfback, Joe Morris, outside of the tight end in a wide split position. I also told him we were going to run “Seventy Protection,” which means we were going to slide the protection to the slot side, and he had to read the hot receiver on the strong side.

“Okay, okay, okay,” Simms said.

“We’re gonna' call patterns and I want you to throw it to Zeke,” I said. Zeke Mowatt was our tight end. He was an up and coming, developing player who unfortunately was injured about his third year. Otherwise, he would have been an outstanding tight end.

When I told Simms to throw it to Zeke, he said, “Every time?!”

“Yeah,” I said. “I want you to throw it to him and I want you to look at him every time.”

Kansas City played a single high safety. No matter what, they always kept the man high but when you put a slot receiver out there, they would put their corners over to the slot. When you put the halfback out wide to the tight end side, their strong safety had to go out there with him.

Now, we had a linebacker covering Zeke. If it was zone, the ’backer would go to his curl zone, but if it was man-to-man, he had Mowatt because the free safety was in the middle, the two corners were over on the slot and the strong safety was out on Morris. So, Zeke was kind of one-on-one with the linebacker.

That had unfolded during the game, but we couldn’t get Simms to see it. Phil was spooked. He wasn’t going to throw it near Albert Lewis or Deron Cherry, no matter how open the guy was. He just couldn’t pull the trigger, so we eliminated that by saying, “Just throw it to Zeke.”

But by telling him, “This is the formation, this is the protection, no problem, just throw it to Zeke,” that narrowed the focus on what he could do. All of a sudden, the light was on. Simms went out there and on the first play he hit Zeke for like 21 or so yards. The next play he hit him for another 20-something yards. After an incompletion, he threw a short pass to Morris, who was on the same side as Zeke.

Then, when they tried to take away Zeke, Simms threw a 22-yard touchdown pass to Bobby Johnson, our split end. We made a defensive stop, got the ball back at maybe our own 20, and Simms hit Zeke a few more times and threw a 3-yard touchdown pass to him to put us ahead, 28-27. Then our defense recovered a fumble, and we won the game, 28-27.

As I was walking through the tunnel, Simms came up to me and said, “Can you believe that?”

“Yeah, I can believe it. We just had to turn the light on for you. Once the light went on, you had it.” To this day, every time I see Simms, I say, “Just throw it to Zeke.”

Even one of the greatest players in NFL history needed the light turned on. Lawrence Taylor was terrorizing the league with the speed rush, speed and power, and teams were starting to split the tackle wider on him, creating more distance between him and the quarterback. Then, because he was such an up-field speed guy, they were running the draws inside, behind where he went, and we were getting hurt with it.

One day before practice, I said to Lawrence, “Do you see what they’re doing? They’re setting you wide. They’re pushing you by the quarterback. You’re back behind the quarterback and it’s the worst position to be because he’s not gonna' throw it backwards, Lawrence.”

When I brought up the draw plays, he said, “Yeah, this draw. What am I supposed to do?”

“You’re supposed to retrace your steps,” I said. “Once you see it’s a draw, just go back the way you came in.”

Our next game was against the Vikings. I’ll never forget it. They ran a draw on him, he recognized it, went back, went inside and made the tackle. And he looked at me and gave me the three-finger with the thumb-index-finger circle, like, “Perfect!”

We had an offensive tackle named John “Jumbo” Elliott. He was a big, strong guy. He wasn’t the best quick-footed guy, but he was 6-7, 310 pounds. He had long arms, he was tough, he was smart.

One day, we were talking about pass protection and I said, “John, do you think any of these pass rushers could push you over backwards?”

“No.”

“Well, if you absolutely get right in front of them, don’t you think you’ve got a good chance to block them? You have to be precise on your pass set. Just get exactly in front of the guy. Once you do that, you win the battle.”

And you know what? He learned that and he would overset the speed rushers and would do everything to get right in front of them. And once they were in front of him, they were not the problem that they were when they were to the side or just off the edge because he was such a powerful guy.

Sometimes as the coach you’re searching for the vehicle to give a player. You see the problem and you know he can’t solve it on his own, so rather than get too complicated we’re trying to go to the lowest common denominator that may solve the problem. “Get in front of the guy … Retrace your steps … Throw it to Zeke.”

That way, there’s not much thinking going on up there anymore. That’s when you turn on the light.

As told to Vic Carucci