Analysis

10/3/23

8 min read

The Proper Way to Evaluate a Rookie Quarterback Class

I read and heard recently a lengthy “instant analysis” of the three rookie starting quarterbacks in the NFL this year: C.J. Stroud of the Houston Texans, Anthony Richardson of the Indianapolis Colts and Bryce Young of the Carolina Panthers.

During my long career in the game, I learned about the evaluation and development of quarterbacks from numerous coaches, scouts and GMs with whom I worked or against whom I competed. Among them were Paul Brown, Jim Finks, Bill Walsh, Bill Parcells, Ted Marchibroda, Marv Levy, Tom Flores, Bruce Arians, Tom Moore and Jim Caldwell.

Using their invaluable input, the organizations with which I worked formulated a series of benchmarks to assess the progress of young quarterbacks. None was based on the first two games of their rookie seasons; no evaluation of any kind was made until the quarterback had played at least eight games, and that solely measured his mechanics, huddle presence and command.

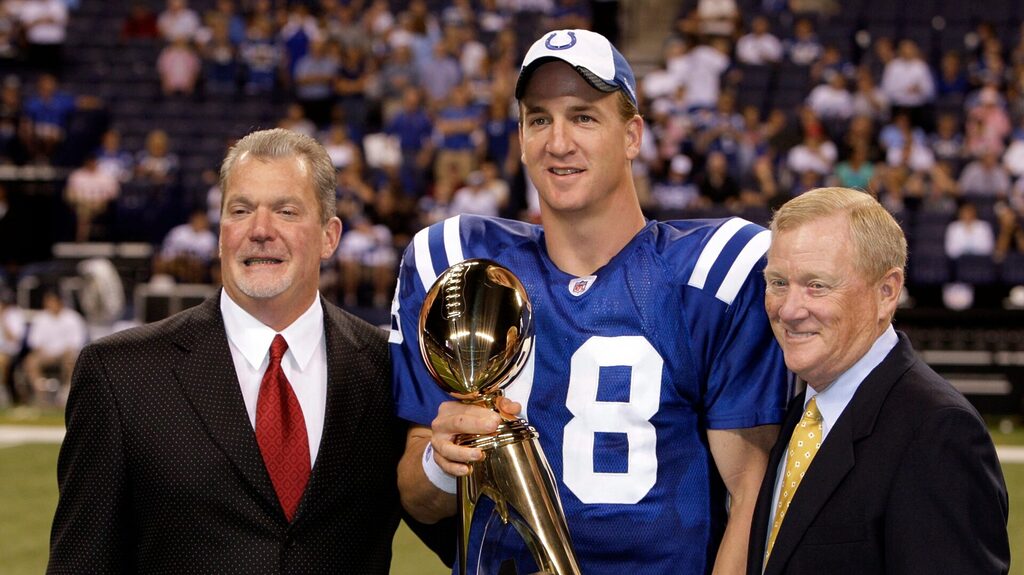

Our first total evaluation was done after the quarterback’s first full season. We set very specific benchmarks for each successive year of the young quarterback's career. If he played from Day 1, as Peyton Manning did, or for three-quarters of his rookie year, as Kerry Collins did, we had lots of film to review. If the quarterback sat for most of his rookie year, as Patrick Mahomes did, you had less game exposure but lots of practice film and meeting exposure on which to base your evaluation.

Today's College Experience Is Insufficient

Compared with those quarterbacks with whom I worked years ago, today’s quarterbacks leave college with much to learn.

Back in the day, Bill Parcells said that he ideally wanted any quarterback he drafted to have started 30 college games and won 70 percent of them. Collins and Manning met that standard. Jim Kelly came to us in Buffalo with two seasons of pro experience in the USFL, albeit in a non-NFL-type offensive system. Collins and Manning had played on excellent college teams and in pro-style systems.

Because of early entry into the NFL, only a rare few quarterbacks meet the 30-game standard. We also see more than a few quarterbacks drafted on physical qualities alone without regard to their win-loss record. In addition, spread offenses changed the skills a college quarterback develops, which are significantly different than many of those skills necessary to win in the NFL.

Mastering Play Calls

Many college teams use the no-huddle attack exclusively, with the only exception being a four-minute offense when the team is ahead and bleeding the clock. Most college quarterbacks do not call their own plays or even vocalize audibles.

Likewise, they rarely change pass protection calls at the line of scrimmage. This is standard practice in the NFL. If collegiate offensive terminology is not short-hand, the quarterback uses the wristband to simply read the call. Either way, he doesn’t have to memorize verbose and arcane nomenclature.

In many NFL offenses, there will be an initial audible key, which is dummy or live based on a code word. (Does “Omaha” sound familiar?) The actual play call or audible follows this.

The quarterback must then set the protection based on the alignment and designate who the key linebacker is based on the protection call. This is called “New Miking.” He must then get a pre-snap read of the secondary alignment to determine what he might face post-snap. Unlike at the college level, every NFL secondary disguises its real post-snap alignment before the snap.

All of this, of course, must be done before the ball is snapped and with the play clock running.

Speaking of snaps, most college quarterbacks have never taken more than a few from under center in their careers. Learning this skill is more difficult than it sounds or appears. Being under center requires different footwork and ball-handling skills in the run game and different timing and footwork in the passing game than in the shotgun.

In short, a rookie quarterback’s transition to the NFL is far more difficult than people outside the game realize. Accordingly, the benchmarks and expectations set by the coaches for these young quarterbacks are vastly different than those promulgated by draft analysts, media and fans.

Year 1 Focus: Fundamentals Rule

Let’s turn to those benchmarks. In Year 1, during OTAs and training camp, we want the rookie quarterbacks to master the nomenclature, take command of the huddle and get the ball snapped cleanly. Identifying defenses and understanding protections will develop as the season progresses.

Many rookie quarterbacks are unable to set protections in their first year. In that case, a veteran center will take that job until the young quarterback can do it. At the moment, Young, Stroud and Richardson — in one form or another — are all struggling in various facets of rookie quarterback adaptation, which is to be expected.

The fundamentals of footwork, which is directly related to accuracy and ball placement, are emphasized in Year 1. The stress of the workload in the regular season tends to erode fundamentals. They must be drilled in every practice. Peyton Manning did the same footwork and delivery drills from the opening day of his first training camp to the last practice of his career.

At the end of a rookie’s first year, we wanted him to be fundamentally sound, understand and be fluent in our nomenclature, command the huddle, get the ball snapped efficiently and have a good grasp of basic NFL defenses.

Interceptions are an occupational hazard. Everyone throws them. We want the experience of Year 1 to help eliminate careless and foolish ones. Statistically and otherwise, we were happy if the arrow was trending up at the end of the season.

Year 2 Focus: Master the Offense, Learn Defenses

The offseason following the rookie season is the most important of a young quarterback’s career. After a much-needed two-month rest to recharge both body and mind, he must be in the team’s building on a regular basis. He will evaluate every play of his rookie year with the coaches. Through this process, he learns to study film analytically. He will master the details of every protection and play, the why of protections and the why and how of executing every concept in the playbook.

All this is done in the classroom. On the field, he must master the fundamentals and mechanics of the position to the highest efficiency level. He will also begin to develop chemistry with each of his receivers. Because of NFL rules, which impede player development, many NFL quarterbacks, such as Tom Brady and Peyton Manning, hold passing camps with their receiving corps at off-site locations to get around these rules.

After Year 2, we want the quarterback to have mastered the offense physically and mentally while at the same time understanding, in detail, what post-snap defenses look like and are trying to do to him. He must also have a thorough understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of his teammates and how to best utilize them. He should also have developed a significant feel for clock management and game strategy.

At the end of Year 2, we wanted the quarterback to have established himself as the person everyone on the field believes can lead them to success.

Year 3 Focus: Operate Every Facet of Offense

In Year 3, our quarterback should have progressed far enough to operate every facet of the offense at a winning level.

He must have — by his work ethic, comportment, efficiency and discipline — established himself as an undisputed leader of the squad. He must have mastered sound clock and game management. And he must have been able to audible out of bad plays and into good ones in every specific game situation.

If he has that special ability to perform at the highest level during the most difficult times, you will see that emerge in Year 3. At the conclusion of Year 3 — and only then — will you know with a firm degree of certainty that you have the person who can lead you to championships.

You may have noticed that at no time did I mention wins and losses. Bill Walsh stated it best in his last and greatest book: If a quarterback masters the many facets of his craft during his early NFL years, “the score takes care of itself.”

When you hear criticism or praise for your rookie quarterback this season, please keep in mind he is a work in progress. Three seasons from now, we will have a full picture of him.

As told to Vic Carucci

Bill Polian is a former front office executive and a six-time Executive of the Year award winner who won Super Bowl XLI with the Indianapolis Colts. Polian’s career as an executive earned him an induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2015.