Analysis

1/9/22

9 min read

How Are NFL Offenses Making Two-Minute Drills Look Casual?

The final two minutes of a half are always the most stress inducing, anxiety riddled moments in all of football. These situations can make or break a team’s chances of winning a game. Yet, players like Peyton Manning – the league record holder for game-winning drives in a career – made them look simple. Routine even!

There is a reason why Head Coaches across the NFL (and the football landscape as a whole) set time aside every week to work on this aspect of the game. In the Super Bowl Era, teams with a lead going into halftime ultimately win the game 78% of the time. Former Chicago Bears Head Coach Marc Trestman used to install his two-minute offense on the first day of OTAs. His rationale was twofold.

First, it gets players active early on and helps to shake off the cobwebs of the offseason. Playing an upbeat style of football can make practice more fun for both offensive and defensive players. Those two-minute scenarios are less indicative of scheme and more closely magnify a player’s (and coach’s) ability to think on the fly and rely on intuition. Players new to the building (i.e. rookies, free agent signings, etc.) who are not familiar with the playbook could still participate and begin to show off their skills.

More importantly, as an offensive play caller, it helped players get accustomed to the kinds of plays he would call in those situations. Trestman wanted his team to master five play calls on Day 1 that would be used over and over in the two-minute drill. These plays might be what coaches call “one worders”, which involve the coach saying just one word that signifies the formation, snap count, protection, and play call.

Practice makes perfect. Given the limited amount of time coaches have in OTAs and training camp to install their systems, it is critical to place a point of emphasis on aspects of the game that are of the highest priority.

Implementing the two-minute offense early can also trickle down to other aspects of play calling, namely in the red zone. Coaches will often take three or four of their redzone play calls and utilize them in the two-minute drill.

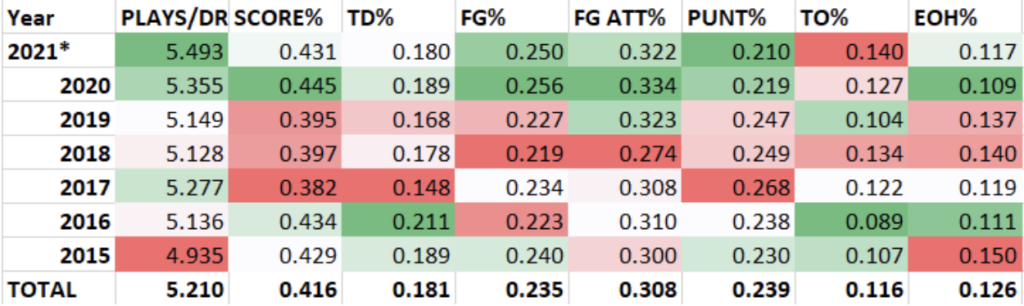

Prior to the 2015 season, the league pushed the line of scrimmage for the point after attempt back to the 15-yard line. Since then, 41.6% of drives at the end of the first half have resulted in a score. In fact, through 15 weeks of the 2021 season, that figure is an even greater 43.1%.

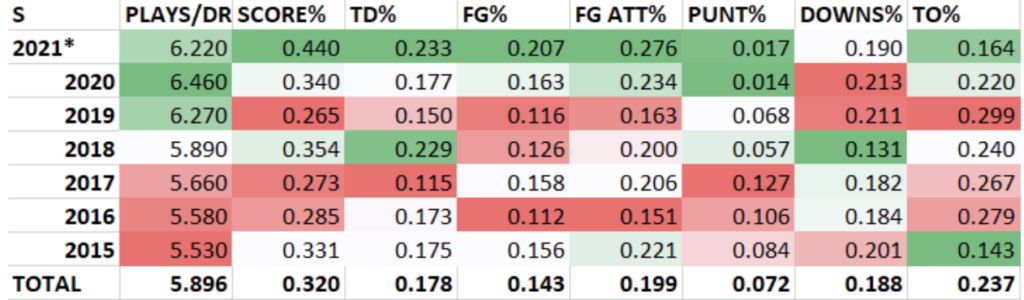

Those figures are consistent with what we see in two-minute drill situations at the end of games by teams who are down one score or tied. In the same seven season time frame since 2015, teams are scoring nearly one third of the time (32%) under such conditions. Year-by-year teams have gotten more efficient in this aspect of the game – with the league’s productivity coming to a head this season. Through 15 weeks, teams trailing by one score or tied in the final two minutes of the fourth quarter have scored on nearly 44% of drives.

Just this past weekend, 19 out of 34 drives in such end of half situations resulted in scores - three of which won their team the game.

These figures beg the question: Why has it gotten easier for teams to score in these pressure-packed spots?

Clock Management

Timeouts

Coach Trestman compares time outs to the process of creating diamonds, stating, “the longer you hold onto them, the more valuable they become.”

Teams across the league have begun assigning someone within the team’s coaching staff or analytics department as a “time management expert”. Delegating this responsibility frees the Head Coach to focus on play calling (if that is his duty) and other decisions that need to be made in a matter of seconds.

There is still a significant level of involvement that a Head Coach retains in deciding when to take a time out and when to hold on for a later point in the game. However, these time management experts are focused on this aspect of clock management from the start of the game until the clock hits 00:00. They are the one with the data to back up whether taking a time out on 3rd & 9 makes sense or to hold on to the precious resource and take a delay of game penalty because the odds of gaining the first down yardage (or scoring on the drive) does not change drastically by losing those 5 yards.

The Head Coach and team’s time management expert must also be in lockstep with the quarterback on the team’s philosophy regarding when to utilize timeouts. If the quarterback panics with time running down on the play clock and burns an unwanted timeout, then all of the Head Coach and time management expert’s collaboration is useless.

With an additional person involved in the usage of timeouts, Head Coaches and play callers can focus on when it makes sense to be aggressive or more reserved before the end of the first half. Time on the clock and field position will often dictate that decision.

Field Position & Time Remaining

In the first half when a drive starts with less than 1 minute, teams decide to run out the clock and take it into halftime more often than not. However, when that threshold is crossed and there is more than a minute left on the clock, teams become much more aggressive – scoring at a 42.63% clip.

In addition to time on the clock, starting field position is certainly an important factor to take into consideration. A majority of drives prior to the end of the first half start on the minus side of the field. Of such drives, 35.57% result in a score. Comparatively, while they occur far less often, two out of every three two-minute drives that begin on the opponent’s side of the field prior to the end of the first half end in a score.

When breaking these groups down into 10-yard increments, the threshold that should give teams confidence that they will score is much farther back than one might imagine. If a drive starts at the offense’s own 30-yard line, they have a 47.42% chance of scoring based on the data from first half two-minute drills over the last 7 seasons. However, this figure decreases dramatically when looking at such drives that begin with less than a minute left in the first half – dropping from 47.42% to 39.82%.

Yet, even if the drive begins on their own 20-yard line, an offense has just less than a 50% chance of either scoring or at least attempting a field goal.

These data points suggest that teams across the league have a good chance of getting points on the board before halftime. Decisions like the one we saw by Kyle Shanahan in last Thursday night’s game between the 49ers and the Titans go against the data – especially with San Francisco holding on to two timeouts.

Offenses

With teams using mainly 11 personnel (84% of plays), offenses have gone to more empty sets in two-minute scenarios in order to mitigate the pass rush. Putting a TE or RB in the slot to chip an edge rusher, rather than lining an RB up in the backfield to take on an untouched rusher 1-on-1, has become the formation “de jour” in recent years. The thinking here is that an RB will be of more use helping to slow down an edge rusher before getting into a short, checkdown route than they will by waiting 3 to 4 yards deep (just in front of the quarterback) to take on an unaccounted-for rusher with a full head of steam. This, in turn, should allow the QB more time to throw in a clean pocket.

The usage of empty formations in 2-minute scenarios has gone up from 8.91% in 2015 to 15.34% through 15 weeks in 2021. With no real threat of the run, especially for a trailing team in the fourth quarter, there is no need for an RB in the backfield.

As a result, 6-man protections have begun to decrease year-to-year. This negative correlation makes sense given that there is not an RB in the backfield that would be a natural 6th protector. However, even with fewer protectors, the average time to throw (TTT) has not decreased much, if at all. From 2015 to now, the only noticeable difference is actually that quarterbacks have 3.5 seconds or more average TTT 2.66% more often. This data point is likely a result of more off-script/scramble plays by mobile quarterbacks, who have become more prevalent in today’s NFL.

Even so, teams have become more adept at moving the ball down the field given these adjustments to offensive personnel and scheme.

Defenses

With TTT remaining the same with less “traditional” protectors staying in to block, quarterbacks have more options to throw to and thus have a higher likelihood of completing a pass. Because defenses cannot take away everything, coordinators have to prioritize who, where, and how to cover when determining their scheme.

Coach Wade Phillips prioritizes keeping the offense in bounds in order to either keep the clock running or force the offense to use their timeouts. Therefore, defenses may be more willing to give up throws underneath in order to prevent the offense from beating them with a deep shot or an intermediate pass to the offense’s top receiver.

As a result, there have been more throws with an average depth of target (ADOT) 4 yards or less and fewer throws 15 yards or more since 2015. Consequently, there have been more plays per drive in both first and second half two-minute situations which could tire out a defense, especially at the end of a game.

Defenses are becoming more and more willing to let offenses dink-and-dunk their way down the field while playing a 2-deep shell concept rather than bringing a blitz and letting a deep pass win the game for the offense. Still, defenses need to get pressure on the quarterback in one way or another. Phillips says 5-man rushes and zone pressures are a good way to accomplish this goal.

There are obvious differences in play calling and decision making between two-minute drills at the end of the first half and the end of the game. However, the key takeaway here is that in a 60-minute game, it often comes down to the final two which determine who will add a tally to the win column. Teams across the league are prioritizing efficiency in the two-minute drill, and it seems to be paying off in the offense’s favor.