Analysis

11/4/21

13 min read

The Evolution of Running Quarterbacks

When Dick Vermeil took the Philadelphia Eagles to the Super Bowl in 1980, his quarterback was Ron Jaworski.

Jaworski was a classic drop-back passer. Speed wasn’t his forte. His nickname was the Polish Rifle not the Polish Roadrunner. He averaged 1.4 rush attempts per game and 3.3 yards per carry during his 15-year NFL career.

Nearly two decades later, when Vermeil won the Super Bowl with the St. Louis Rams, it was with another seven-step-drop, stay-in-the-pocket quarterback, Kurt Warner. Warner, who went into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2017, rushed for 92 yards on 23 carries during the Rams’ ‘99 Super Bowl run.

“I used to think – and I was wrong – I used to believe that if a quarterback can run he will run,” Vermeil said recently. “If he can’t, he’ll stay with the discipline of the play and stay in the pocket. He’ll get hit more, but he’ll stay with his progressions and end up with more good plays. That’s what I believed then.”

Vermeil, who is a finalist for the Hall of Fame himself this year, hardly was alone in that conviction. Most college quarterbacks who could run, the overwhelming majority of whom happened to be Black, typically were switched to wide receiver or running back or cornerback when they got to the NFL.

A whole new game

Much has changed since then. For starters, more than a third of the league’s starting quarterbacks currently are Black. And the days of the drop-back passer, well, with a few exceptions, they’re going the way of the dinosaur.

A league that once spurned athletic quarterbacks now embraces them. Today’s NFL offenses don’t look all that much different than college offenses.

For the first time in the modern era of the NFL, there currently are seven quarterbacks among the league’s top 50 rushers – the Ravens’ Lamar Jackson (9th, 480 yards), the Eagles’ Jalen Hurts (17th, 432), the Bills’ Josh Allen (39th, 269), the Bears’ Justin Fields (43rd, 243), the Giants’ Daniel Jones (44th, 241), Washington’s Taylor Heinicke (45th, 232) and the Chiefs’ Patrick Mahomes (48th, 229). Last year, there were six in the top 50.

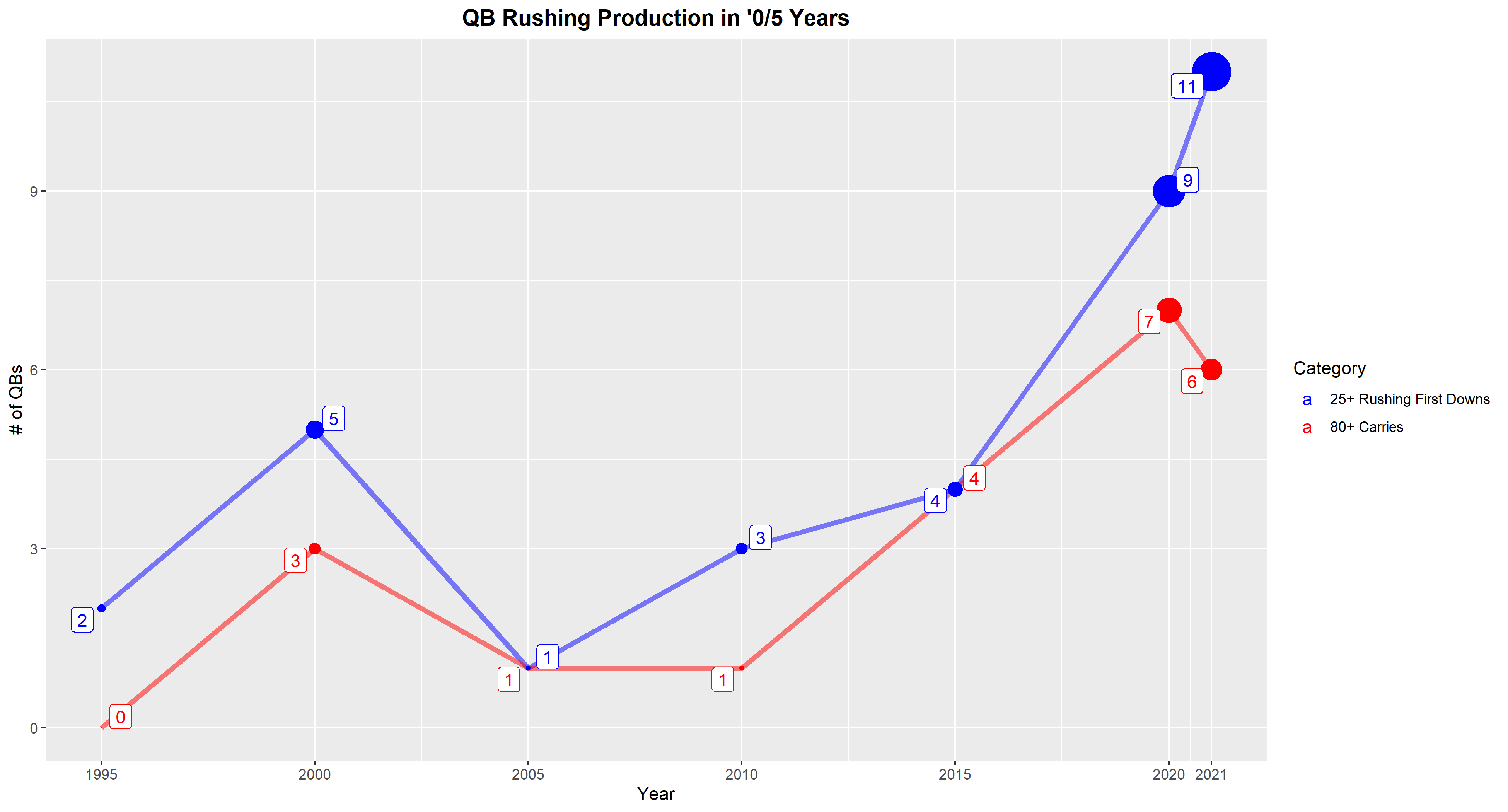

Six quarterbacks are on pace to have 80-plus rushing attempts this season, including four – Jackson, Hurts, Allen and the Cardinals’ Kyler Murray -- who are on a 100-carry pace. And a record 11 quarterbacks are on pace to have 25 or more rushing first downs.

Long overdue

“This league could have had this so many years ago,” said Charles Davis, who is part of CBS’s No. 2 NFL broadcast crew with Ian Eagle. “This may be new to the NFL, but it’s not new to the game. The opportunity existed long, long ago. But those people were turned into wide receivers and defensive backs and running backs.

“You can go way back. Eldridge Dickey never should have had to switch positions. Marlin Briscoe could have been left at quarterback instead of being turned into an All-Pro receiver. You could play that game with dozens of guys over the years."

Dickey was a standout quarterback at Tennessee State. He was the first Black quarterback taken in the first round of the NFL or AFL drafts (by the Raiders in 1968), but was quickly moved to wide receiver.

Same with Briscoe, who started five games at quarterback as a rookie with the Denver Broncos in ’68, then spent the rest of his career as a wideout.

“The NFL was way late [on embracing quarterbacks who could run],” said Daniel Jeremiah, the senior draft analyst for the NFL Network and a former scout for the Ravens and Eagles. “But they eventually figured it out. They finally realized that instead of asking all of these guys who are incredibly athletic, to fit into their mold, they started changing the mold and going back and incorporating what makes these guys comfortable, at least early in their careers.

“To me, it’s a major red flag now when you have a guy who can’t do all of the [athletic] stuff. It’s kind of totally flipped.

“It’s not like they’re saying you’ve got to play this style, this way, your whole career. But early on, let’s do things, let’s incorporate the RPOs and the zone-reads and let you just get comfortable with the stuff you did in college, and then you’ll eventually grow into being able to do more things. It’s been a great way to get these guys on the field right away. And obviously, there’s a bunch of them.”

Embracing the college game

For years, most NFL coaches were inflexible in their thinking when it came to their offensive systems and the quarterbacks that ran them. You either fit their system or you didn’t. Adjusting the system to fit the quarterback’s skill-set seldom was a consideration.

And then, slowly, but surely, things changed. NFL coaches started stealing more and more things from the college game, until there wasn’t much of a difference between the two.

“I’m not a huge proponent of the college and pro games being homogenized, meaning they look the same,” Davis said. “I like the fact that there are differences between the two and how they’re played and how people consume them and the whole deal. I kind of like that.

“But I don’t know that offensively, there’s much difference between the college and pro games now, save for the (college) teams that are pure option teams. Other than that, the game on both levels never has been more quarterback-centric than it is now. Everything runs through the quarterback.”

And if the quarterback happens to be athletic and can move the sticks with his legs as well as his arm, more power to him.

Ravens head coach John Harbaugh won a Super Bowl in 2012 with Joe Flacco as his quarterback. Flacco, like Jaworski and Warner, is a pure pocket passer. He’d be hard-pressed to outrun a parked car.

Six years after that Super Bowl win, however, Harbaugh and the Ravens drafted the anti-Flacco, Lamar Jackson. In the weeks leading up to the draft, Harbaugh met with his offensive coaches and challenged them to present him with a plan for using the versatile Jackson if they did indeed take him.

“I thought that was excellent thinking,” Davis said. “Because in the past, if you had been presented with a Lamar Jackson, you would’ve had a staff say like, what do we do with this? In our offense, the quarterback drops back 3-5-7 steps. We set up the pocket and throw it. If he can’t adapt to that, we can’t use him. Well, no one is doing that anymore.”

Run, Lamar, run

Jackson has averaged 10.5 rushing attempts per game since replacing Flacco as the Ravens’ starter midway through the ’18 season. He’s well on his way to his third 1,000-yard rushing season in four years.

Jackson is different than most of the other running quarterbacks in the league in that there have been no indications that the Ravens plan to have him cut back on his running any time soon, as opposed to someone like the Seahawks’ Russell Wilson, who averaged 6.4 rushing attempts per game in his first four seasons, but just 4.8 in the last six.

“I don’t know that we’re going to see many other people put up the kind of numbers Lamar is putting up,” Davis said. “That is a flat-out, full-on commitment that your offense is really, truly going to be run through him, both the pass and run game.

“Lamar, in a sense, is your old single-wing tailback. He’s going to get those kind of touches. Everything he does isn’t a scramble. There’s a lot of called quarterback runs. A lot of other teams aren’t going to do that, at least to the extent Baltimore is.

“Justin Herbert is pretty darn mobile. But there’s no way the Chargers are going to call 15 run plays for him in a game. Baltimore? Sure. That’s who they are. And (Ravens offensive coordinator) Greg Roman and his crew have fashioned their offense that way.

“Aaron Rodgers, even in his youth, Green Bay wasn’t going to do that. I can go right on down the list. Let’s say Philadelphia fully commits to Jalen Hurts and decides he’s their guy for the next 5-7 years. I don’t know that Nick Sirianni is going to call 15 run plays for him.

“Baltimore’s commitment to it, their culture with it, it’s a whole different ball game. And I actually admire it from afar. I mean, look at how they’re winning this year, and you and I could get tryouts at running back because of all the injuries they’ve had. Their commitment to [Jackson running] is off the charts. They’re saying, ‘This is who we are and we’re going to continue to be that team.’”

The Eagles’ Hurts has averaged 9.9 rush attempts per game in his first 12 NFL starts. He’s rushed for 30 or more yards in all 12 of those games, and 60 or more yards in seven.

Can’t run? Can’t play

The first five quarterbacks taken in the 2018 draft were Baker Mayfield, Sam Darnold, Josh Allen, Josh Rosen and Jackson. The only one of those five who isn’t currently starting also happens to be the only one who can’t run: Rosen. The former UCLA quarterback is on his fifth team after signing with the Falcons in August.

“Josh was the old-school, pure pocket passer,” Jeremiah said. “But he doesn’t have any twitch or explosiveness. It’s hard to play with one of those guys now.

“The only pure pocket passers in the NFL right now are guys who have been in the league for 15 years and have so much knowledge and experience that it allows them to make up for their lack of athleticism. As a young guy coming into the league, if you’re not athletic and don’t have that experience, you’ve got no shot.”

Jeremiah also pointed out that the colleges are producing difference-making defensive linemen at a much higher clip than offensive linemen who can block them.

“If you can’t play under duress,” he said. “you can’t play.”

A few mobile quarterbacks started to pop up in the league in the ‘80s and ‘90s, but not a lot. None were more exciting to watch or more problematic to defend than the Eagles’ Randall Cunningham.

Randall was dubbed “The Ultimate Weapon” by Sports Illustrated in 1989. He rushed for 500-plus yards six straight years, including 942 in 1990. Averaged a league-best 8.0 yards per carry on 118 attempts in ’90.

But through most of the ‘90s, quarterbacks like Cunningham were the exception rather than the rule. That started to change in ’99 with the drafting of Donovan McNabb and Daunte Culpepper. Then, two years later, The Michael Vick Experience arrived.

“There had to be an acceptance somewhere, and a full-blown opportunity for that [kind of] guy,” Davis said. “And Vick was it. He was the final piece.

“McNabb and Culpepper could run, but they still made the majority of their plays in the pocket. Were they mobile? Yeah. But the Michael Vick Experience just took everyone’s breath away.”

The Michael Vick Experience

Vick averaged nearly 11 carries a game in his two seasons as a starter at Virginia Tech. He rushed for nearly 1,300 yards and 17 TDs and led the Hokies to the national championship game. The Falcons made him the first overall pick in the 2001 draft.

“The guy could fly,” Davis said. “And the way he threw the football. Just a little flick and whoosh. That ball took off. After Michael came along, everybody was saying, ‘Can I get one of those?’ Because he gave defensive coordinators headaches. The coordinator would go to his head coach and say, ‘I don’t know what I’m going to do with this guy.’”

Vick rushed for 6,109 yards in his career, the most ever by an NFL quarterback. His 347 rushing first downs also the most. Jackson likely will eventually shatter both marks.

But while there were other quarterbacks in the league who could run, there still was a reluctance to let them, mainly because coaches were afraid of them getting hurt. In 2005, Vick was the only quarterback with 80-plus carries (103) or 25-plus rushing first downs (43).

Five years later, Vick, then with the Eagles after serving two years in prison for running a dog-fighting ring, still was the only quarterback with 80 carries, and one of just three quarterbacks, along with the Bucs’ Josh Freeman and the Jaguars’ David Garrard, to have 25 rushing first downs.

Jeremiah thinks it was Russell Wilson who finally convinced NFL coaches it was OK to let your quarterback run with the ball.

“Russell was the first guy to have that athleticism and mobility who also proved he could do everything in the passing game that you wanted him to do as well,” Jeremiah said. “So, it was a cake-and-eat-it-too situation with somebody like him.

“You had the size. So, you could throw out all of those arguments about him not being big enough [to take hits] and not fitting a prototype. And he proved he could win at a high level. Once that happened, it was, OK, let’s just find good quarterbacks. Let’s not get hung up on finding throwers. Let’s expand our definition of the word quarterback. That’s what Russell did.”

In 2015, Wilson was one of four quarterbacks with 80 or more carries and one of four with 25 or more rushing first downs.

Last year, he was one of seven with 80 carries and one of nine with 25 rushing first downs.

No injury concerns

“These guys coming out now have been doing this in high school and college,” Davis said. “They understand where the traffic is coming from. They know where the heat is coming from.

“A lot of coaches also protect them. These rollouts and bootleg, teams are doing a lot of what we call waggles where you pull the guard with the quarterback to give him an extra protector. How many times do you see the tight end motion back inside and become the personal protector and escort [for the quarterback] on some of these run plays?

“So, teams have gotten very creative with it. You can’t totally eliminate the injury factor. But we also know that we’ve lost a good number of quarterbacks for a good number of years who were standing in the pocket and got drilled by a blindside hit or had a lineman roll up on the back of their leg.

“It’s still going to happen. But you account for that by who your backup is. If you want to continue to run the same style of offense, your backup has to be a similar type of guy or give you some of those traits. Or you may have a different package for him and play a different style with him.”