Analysis

12/9/21

9 min read

Behind The Line: How The Short Passing Game Has Changed The NFL

Ron Jaworski played quarterback in the NFL for 15 years, from 1974 to 1989. Was pretty damn good. Started 143 games. Threw for 179 touchdowns and more than 28,000 yards. Had a 53.1 career completion percentage.

“In my era, if you completed 60 percent of your passes, you had a fantastic year,” said Jaworski, who topped out at 58.4 in 1982. “I was with Dick Vermeil a few weeks ago. We were chewing the fat and he said, ‘Ron, with your arm and accuracy, you would have a 75 percent completion percentage against today’s defenses.’”

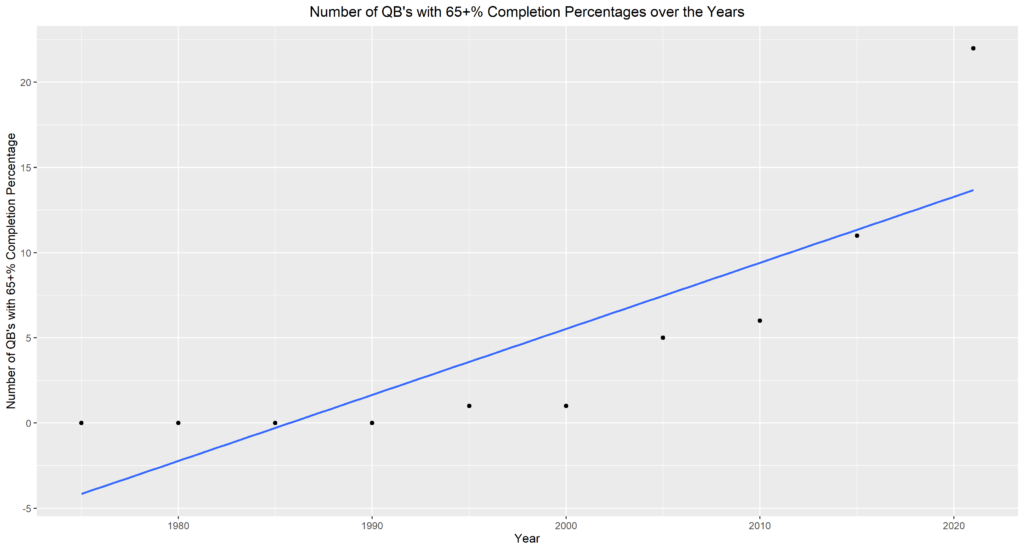

In Jaworski’s last year in the league in ’89, just one quarterback – Joe Montana – had a completion rate above 65 percent, and only five finished above 60 percent.

Compare that to this season where three quarterbacks currently have completion rates above 70 percent, another 19 are above 65 percent and a total of 31 – 31! – are above 60 percent.

The average completion percentage in the league this season is 65.2, equaling last season’s all-time high. Ten years ago, it was 60.1. Twenty years ago, it was 59.0. Thirty years ago, it was 57.4.

“The rules have been a big, big part of that,” Jaworski, a longtime football analyst said of the soaring completion percentages. “The restrictions on physicality of defensive players. You can’t touch a guy. You can’t re-route him down the field. You can’t hit the quarterback. All of those things have come into play.

“But the biggest difference has been the screen game.”

Screen usage – particularly bubble screens – have shot up in the last 10-15 years, and with it, completion rates.

SCREEN IMPACT

The popularity of the screen game has dramatically inflated quarterback completion percentages. A look at screen use this season, along with team-by-team completion percentages with – and without – the screen:

| Team | Screen Pct. | Overall Comp. Pct. | Comp. Pct. Minus Screens |

| Cardinals | 18.2 | 73.3 | 69.1 |

| Packers | 15.7 | 65.5 | 61.3 |

| Bucs | 15.1 | 68.5 | 64.2 |

| Eagles | 14.2 | 61.5 | 56.1 |

| Colts | 12.4 | 63.1 | 60.5 |

| Browns | 12 | 62.2 | 58 |

| Chiefs | 11.7 | 64.8 | 61.2 |

| Rams | 11.7 | 66.2 | 62.7 |

| Saints | 11.5 | 57.3 | 54.6 |

| Panthers | 11.3 | 57.3 | 55.5 |

| 49ers | 11.1 | 64.8 | 62.8 |

| Lions | 11.1 | 66.5 | 64.5 |

| Giants | 11.1 | 62.9 | 58.5 |

| Patriots | 11 | 70.8 | 68.5 |

| Jaguars | 10.8 | 58.2 | 54.7 |

| Texans | 10.7 | 63.2 | 60.5 |

| Bills | 10.7 | 65.6 | 62.8 |

| Titans | 10.7 | 65.8 | 64.2 |

| Vikings | 10.6 | 68.2 | 65.7 |

| Jets | 10.5 | 61.7 | 58.4 |

| Washington | 10.4 | 67.7 | 64.7 |

| Cowboys | 10.4 | 68.6 | 66.1 |

| Seahawks | 10.3 | 67.5 | 64.4 |

| Steelers | 9.3 | 64.2 | 61.4 |

| Bengals | 8.8 | 68.2 | 66.3 |

| Raiders | 7.9 | 67.8 | 65.9 |

| Dolphins | 7.3 | 67.1 | 65.4 |

| Bears | 7 | 60.7 | 58.3 |

| Chargers | 6.9 | 66.5 | 64.8 |

| Broncos | 6.4 | 66.6 | 66.4 |

| Falcons | 5.1 | 66.5 | 66 |

| Ravens | 4.6 | 64.2 | 62.8 |

In 2010, screens accounted for 7.6 percent of the total quarterback dropbacks in the league, according to Pro Football Focus. This season, it’s up to 10.4.

But it’s not just screens. With the pass-rushers getting bigger and faster, offenses are relying more on short, quick high-percentage throws. Get the ball to a receiver in space and let him do his thing.

In the last eight years, the percentage of pass attempts of three yards or less in the league has jumped from 29.1 in 2013 to 33.3 this year. Twenty-eight quarterbacks have had at least 30 percent of their throws this season travel no more than three yards beyond the line of scrimmage.

“Back when I was playing, with the exception of a screen here and there, I don’t remember throwing many balls at or around the line of scrimmage,” said Rich Gannon, a four-time Pro Bowl quarterback and the NFL MVP in 2002 with the Oakland Raiders.

“We would throw a hitch or slant or drag route. But everything has changed. The college game has invaded the NFL. These coaches aren’t stupid. Look at the way they’re able to generate explosive plays by throwing the ball to a receiver out on the perimeter at the line of scrimmage. You get a guard or tackle out in front of him or two other receivers blocking, and the next thing you know you’ve got a big gain.”

DINKING AND DUNKING

A 12-year breakdown of league-wide screen use and overall throws of three yards or less:

| Year | Screen Pct. | Pct. of Att. 3 yards or less |

| 2021 | 10.4 | 33.3 |

| 2020 | 9.4 | 32.6 |

| 2019 | 9.7 | 31.1 |

| 2018 | 10.2 | 32.4 |

| 2017 | 9.3 | 31.3 |

| 2016 | 8.2 | 30.3 |

| 2015 | 8.9 | 31.2 |

| 2014 | 8.8 | 31.8 |

| 2013 | 7.6 | 29.1 |

| 2012 | 8.5 | 29.5 |

| 2011 | 8.2 | 29.1 |

| 2010 | 7.6 | 30.8 |

Gannon had a 67.6 completion percentage when he was the league MVP in ’02. He was one of just four quarterbacks that year with a completion rate above 65.0. To that point, just three quarterbacks in history ever had a 70 percent completion rate – Ken Anderson in 1982 (70.6), Joe Montana in 1989 (70.2) and Steve Young in 1994.

“When I was playing, our (completion rate) goal was 65 percent. But if you were at 62-63, you were doing really good. You see the numbers today creeping up and creeping up. There’s only a handful of quarterbacks in the league who are south of 60 percent. And those are the guys that are either not very good or just rookies or whatever.”

Gannon agrees with Jaworski. It’s not that quarterbacks are that much more accurate today than they were back when the two of them played. They’re just benefitting from the rule changes that have restricted defenses and the skyrocketing popularity of screens and short throws that have inflated completion percentages.

Remove screens and short high-percentage throws from the equation and the completion percentage of quarterbacks drops anywhere from three to eight points.

“Tua (Tagovailoa of the Dolphins) is second in the league in completion percentage right now,” said Gannon, who spent 16 years as an analyst on NFL games for CBS. “If you break down his throws, a third of them have been at or close to the line of scrimmage.”

The Dolphins are 27th in screen usage (7.3%), and Tagovailoa is 24th in percentage of throws behind the line of scrimmage (20.4). But he’s sixth in percentage of throws of three yards or less (36.4) and fourth in throws of five yards or less (48.5). He has the third lowest percentage of 20-plus yard throws (6.9).

It’s not just young quarterbacks like Tagovailoa that are relying heavily on screens and dinks and dunks. The Steelers’ Ben Roethlisberger leads the league in percentage of throws of three yards or less (41.2). The Packers’ Aaron Rodgers is second at 38.6.

Rodgers leads the league in percentage of throws behind the line of scrimmage (30.0) followed by the Chiefs’ Patrick Mahomes (29.9) and the Cardinals’ Kyler Murray (29.2). Murray has the league’s best completion percentage through 13 weeks (72.7).

THE LONG AND SHORT OF IT

An NFL-high 30 percent of Aaron Rodgers’ passes this season have been to receivers behind the line of scrimmage. But he also has the fifth highest percentage of 20-plus yard throws. A breakdown of the league’s quarterbacks:

| Player | Team | Pct. Of Throws Behind LOS | Pct. Of 20+ Yard Throws |

| Rodgers | Packers | 30 | 13.9 |

| Mahomes | Chiefs | 29.9 | 10.7 |

| Murray | Cardinals | 29.2 | 14.8 |

| Siemian | Saints | 27.2 | 11.6 |

| Hurts | Eagles | 27.1 | 13.4 |

| Goff | Lions | 26.8 | 9.3 |

| Mills | Texans | 26 | 9.4 |

| Cousins | Vikings | 25.6 | 11.5 |

| Roethlisberger | Steelers | 25.5 | 10.8 |

| Heinecke | Washington | 25.2 | 12.5 |

| Brady | Bucs | 24.8 | 10.6 |

| Carr | Raiders | 24.6 | 13.1 |

| Wentz | Colts | 24.3 | 11.9 |

| R. Wilson | Seahawks | 23.9 | 15.4 |

| Allen | Bills | 23.4 | 11.4 |

| Lawrence | Jaguars | 23.5 | 9.6 |

| Darnold | Panthers | 23.2 | 9.8 |

| Mayfield | Browns | 22.8 | 15.1 |

| M. Jones | Patriots | 22.7 | 10.9 |

| D. Jones | Giants | 21.6 | 6.6 |

| Prescott | Cowboys | 21.2 | 12.5 |

| Herbert | Chargers | 21.2 | 8.7 |

| Z.Wilson | Jets | 20.6 | 12.8 |

| Tagovailoa | Dolphins | 20.4 | 6.9 |

| Bridgewater | Broncos | 20.3 | 11.3 |

| Burrow | Bengals | 20.1 | 11.6 |

| Brissett | Dolphins | 20 | 8.9 |

| Ryan | Falcons | 19.8 | 6.2 |

| Tannehill | Titans | 19.6 | 7.5 |

| Stafford | Rams | 19.6 | 11 |

| Garoppolo | 49ers | 17.7 | 7.1 |

| Jackson | Ravens | 16.9 | 14 |

| Fields | Bears | 14.1 | 18.2 |

The bubble screen has been around for a long time, but its popularity has really taken off over the last few years as coaches have looked for the easiest ways to get the ball in the hands of their playmakers.

“(The bubble screen) was a part of our game, but not a big part of it; not like it is now,” Jaworski said. “Teams are using it to get the ball out on the perimeter. It’s basically a long handoff.”

“You’re trying to find drive-starters,” Gannon said. “You’re trying to find a way to get the quarterback off to a good start. You also want to get your best players touches and get them the ball in space.

‘If you notice, a lot of the (bubble screens) are on first down because they’re nothing more than perimeter runs. They’re looking for a way to get 4-5 yards on first down. They can do that just as easily by throwing the ball on the perimeter to the receiver than by handing it to the running back. And the upside for a big play is greater (with a bubble screen).”

NFL coaches aren’t as inflexible as they once were. It’s no longer my way or the highway. They are fitting their systems to their players rather than the other way around. That often means taking what players did well in college and using it now.

“Coaches are implementing things guys used in college,” Gannon said. “You have a wide receiver who was really good running [bubble screens] in college? Well, let’s have him run it here. Let’s make sure we have it in our package.

“Not only that, but you have quarterbacks that did it in college and get it and understand it. Smart coaches always take into consideration what the quarterback did. What are the things he’s comfortable with? What are the things he’s had success with?

“If you have a receiver that’s fast and quick and sudden, if you get them the ball with a couple of blockers out in front, they have the ability to make people miss. It’s a very low-risk, high completion type of play. If you get them the ball in space, what starts out as a one-yard or behind-the-line-of-scrimmage throw can go for 45-50 yards.”

The popularity of the bubble screen also is forcing teams to rethink the type of cornerbacks they’re looking for. Not so long ago, teams were willing to overlook a corner’s ability and/or willingness to tackle if he was an exceptional cover guy. Now, not so much.

“You better have physical corners,” Jaworski said. “And for the most part, corners aren’t physical. They’re cover guys. That’s what they want to do. If you make them defend the run, they don’t like sticking their nose in there. They don’t want to get down and dirty. It’s just the nature of those guys. If, all of a sudden, they have to get up there and take people on and take on blockers and make tackles in the open field, that’s not something they want to do.

“And then scheme-wise, it forces a defense to not blitz as much because so many teams are running the bubbles. I mean, even back when I was playing, if you saw a blitz coming, it was an automatic audible to get the ball out of my hands and into the hands of a playmaker on the perimeter.”